BlogRSS

Neat and Tidy: the Housemaid Uniform

That of the housemaid was the second largest category of employment in Victorian England. A position developed in the rigid and articulated structure of the domestic work, it was defined by strict rules, customs and a proper costume.

School Uniforms

The historical origin of school uniforms has its roots in 16th Century England, when Uniforms were first instituted at the charity schools for poor children, in part to recognise them and also because it was easier and cheaper then buy them ordinary clothes.

The Vivandières: female protagonists of a men’s world

When we think about the army, what usually comes to mind are images of male soldiers dressed in uniforms, indicating their country, their political affiliation or ideological beliefs. However, the army is a community and, as a diversified and complex community, it is – and was – made up by representatives of both genders, who work together and share spaces, time and, interestingly, style.

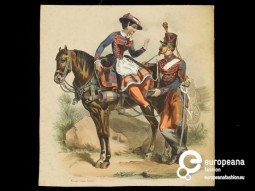

Hand-coloured lithograph depicting a soldier and, on horseback, a cantinière of the French Army, Fortune after a drawing by Hippolyte Lalaisse, ca. 1855, Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum CC BY SA

Vivandières – or cantinières – were originally associated with French regiments, but they were present in many different countries as fundamental part of the army. They had several tasks, not only carrying food and drinks to soldiers on the battlefield, but also acting as nurses and supporters of the troops. They were accounted as important members of their regiment, as underlined by historian Thomas Cardoza, who has researched extensively on the topic. Their importance within the environment of the regiment is in some way proved by their ‘official’ appearance – their uniform – which made them more than mere camp-followers, not only participating in the every-day activities of the army, but living the experience as protagonists.

Vivandières’ uniforms were modelled after those of the regiment they served; this tells a lot about how they considered their role, as ‘soldiers’ belonging to the army, whose identity was constructed not only through their occupation, but also through their attire. Their outfit was usually composed by a jacket and a blouse, which could be tight or loose- fitting depending on the regiments they belonged to; trousers could also be either straight legged or full and wide legged, gathered at the ankle or below the knee; a knee-length skirt was usually over the trousers. As for the accessories, they had great importance in completing the look: the most iconic accessory is for sure the brandy barrel, called tonnelet, which was a unifying element in defining the cantinières across different regiments. Vivandières also used to wear hats, either ‘kepis’ or brimmed. Their uniform fulfils two main aspects required to army clothing – and uniforms more generally: it serves as ‘sign’, defining the identity of vivandières as members of a precise regiment, and it is also practical, allowing them the possibility to move and ride more freely than they would do wearing ‘civilian’ female clothing.

Hand-coloured lithograph of a vivandière of the French Army, ca. 1850-70, Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum CC BY SA

At the end of nineteenth century cantinières were forced by regulations to replace their attires with plain grey dresses and metal identification plaques. Despite their popularity, they were banned in 1906 by the French War Ministry. Vivandières’ image anyway remained strongly present in popular culture, theatre, opera and advertising. The Victoria & Albert museum holds a collection of coloured lithographs depicting vivandières in different attires; Browse the Europeana Fashion portal to discover more about this – too often forgotten – feminine presence in what is usually considered ‘a men’s world’.

Between Creativity and Socialism: Aleksandar Joksimovic

Fashion in the era of socialism and the example of the creator explains how the political power, the economic forces and fashion were inevitably connected. After World War II, the Eastern European socialist regimes embraced early Bolshevik ideology, and decidedly rejected Western style of dress. The regimes then had to establish a new dominant style which included practical, simple and classless clothing intended for the working woman.

Dissatisfied with the domestic industry and unfashionable clothes they had been imposed, people turned to private tailors, homemade clothing or to the black market. Soon the country struck a discrepancy between production and consumption. The situation improved in the early 60s, thanks to shopping tours in Trieste, commercial advertisements and, above all, the rise of a new middle class fascinated with Western consumer habits. In all the Yugoslavian territory the desire for individualism was strong, as testified by the articles appeared on the Belgrade newspaper Bazar. The first fashion designer in the Yugoslav territory who directly addressed the need for a change in fashion was Aleksandar Joksimovic.

Aleksandar Joksimovic is one of the most widely known designers in Yugoslavia, not only for his designs, but above all for his ability to conjugate, in his designs, traditions and innovation. Joksimović graduated in 1958 in textile design from the College of Applied Arts in Novi Sad, after a short period studying scenography. After working as designer of work uniforms for the City of Belgrade Institute for Household Improvement, In 1963 he designed his first evening wear collection. His designs received appraisal by the critics, who valued above all his creativity, and this made him a prominent personality in the Yugoslavian fashion system. Joksimović was one of the founders of the National Salon within the institute. In 1964, he started working with the Centrotekstil, Yugoslavia’s export-import giant, but kept his role as ‘couturier’ within the National Salon: his designs were appreciated both by the market and by the political power, since they came from the encounter of fashionable cuts and shapes with traditional motifs and decorations. Joksimović was successful in understanding the social change that was happening in Yugoslavia — and precisely, the needs of the rising middle class – while paying respect to the state ideology, including details from folk costumes in his creations.

Photograph of the Damned Jerina (Prokleta Jerina) collection for the Serbian issue of Elle magazine, 1969, Courtesy Museum of Applied Art, Belgrade

His most successful collection were three, presented between 1967 and 1969: Simonides, Stained Glass and Jerina. They were featured on many western fashion magazines, and marked a radical change of the concept of high fashion in socialist Yugoslavia.

Drawing for the Damned Jerina (Prokleta Jerina) collection, 1969, Courtesy Museum of Applied Art, Belgrade

Simonides was the first ‘haute couture’ collection of socialist Yugoslavia. It was presented to the Belgrade audience on 7 March 1967. The collection featured pearls, complicated embroidery and prints and simple, neat cuts, with more constructed ‘bell’ sleeves, inspired by medieval Byzantine clothing and serbian traditional attire. Stained glass and Landscape took inspiration from the coloured glass windows with Orthodox and Catholic monasteries. The collection was showcased at the luxurious fashion Feast of the Leningrad and the exhibition hall of the Belgrade Fair, and it was also screened in Zagreb and Ljubljana. Jerina, presented in 1969, included reference to the latest designs presented in paris by the Pierre Cardin, but was described as an ode to the legendary construction of the city of Smederevo, demonstrating how the designer was alienating aligning the meaning of his collections to the general promotion of the state put in action by the regime.

La Petite Robe Noire: a timeless uniform

In 1926 American Vogue published a picture of a short black dress designed by Coco Chanel with the name of ‘Chanel’s Ford’. Simple and accessible for women of most social classes, Vogue also wrote that it would become “a sort of uniform for all women of taste”.

After its launch in the 1920s as an unavoidable object in a woman’s wardrobe, the little black dress was largely adopted during the Great Depression from women across different social classes, thanks to its affordability and elegance. In fact, it required only two yards of fabric, as opposed to the ten or more yards necessary to fashion bustles; also the darker shades were more practical to work outside the home, not fearing the dirt of the industrial world. For the same reasons, it became a common uniform for civilian women entering the workforce during WW2, when the rationing of textiles was established.

Hollywood’s influence on fashion in North America opened the way to the success of this particular dress. The Chanel’s baton was picked up by Christian Dior, who the petit robe noir as a landmark model for the development of his famous Corolle line, in 1947, demonsrating how the model was prone to modifications and updates. It was Audrey Hepburn who made the garment famous in its original design, wearing the one designed by Hubert de Givenchy in the iconic movie Breakfast at Tiffany in 1960s; Hepburn – and the movie itself – translated the petite robe noir into an icon of popular culture, making it the uniform of choice for women, mo matter the occasion, the space or the time.

However remaining a staple of wardrobes throughout the 1970s, it was the popularity of casual fabrics and the rise of business wear to fully bring back the little black dress into vogue in the 1980s with some ‘twists’: broad shoulders, peplum cut or other embellishments. Due to its being a symbol of glamourous and mysterious women with a strong character, it was adopted later in 1990s by the grunge culture in combination both with sandals or combat boots. In the late 1990s the new glamour trend led to new variations of the dress, culminating with the reemergence of the ‘original’- simple and, of course, full-black – version in the late 2000s.

Until 1920s women used to wear black dresses while mourning, but the simple-yet-elegant design kept by the little black dress through the years has signed the transition of black from a symbol of grief to a statement of high fashion. While it totally disappeared from funerals, it turned into the colour of official occasion, becoming a sartorial staple for most contemporary women.

Discover more glamourous samples of little black dress on the Europeana Fashion portal!

Private Uniforms: The Banyan

Uniforms are usually conceived for public appearances; in the semi-private space of the house, however, people – and especially men – still wear a uniform, but of another kind: what happens here is another kind of performance, where to balance authenticity, self-construction and awareness, and the message to communicate to the people coming to visit. In both cases, the home becomes a stage, where dresses especially designed for the house are the essential props for the success of the act.

Banyans – nightgowns or, to use the fashionable french expression, Robe de Chambre – became very popular in the second half of 17th century; they were used by rich merchants and by members of the aristocracy, and very soon acquired a highly emblematic value, becoming the uniform of the intellectual. In fact, many authors refer in their writings to their ‘dear robe de chambre’. Not only mentioning them in writings, men of letters often decide to be depicted in portraits wearing their banyans. The robe de chambre is regarded as a tool for the exercise of intellectual faculties, and as a tool it has to be comfortable, allowing movement, and large enough to favour the freedom of the body – as well as of the mind. Banyans seem to go out of fashion around 1870, this being confirmed by the quantity of caricatures portraying men of letters in their excessive and lavish nightgown.

The changing nature of the intellectual goes hand in hand with the change in shape of dressing gowns. The rigorous son of the Enlightenment is replaced by the tormented soul of the romantic and followed by the disillusioned and ‘deeply superficial’ dandy. Born between the avenues and the mirrors of the new metropolis, the new intellectuals are extremely interested in their appearance, which has become both their otium and their negotium, and this undoubtedly weighed on the direction taken by men’s fashion from the beginning of the nineteenth century onwards. This is true also for the shape and construction of banyans and home attire in general.

Fashion plate depicting two men in casual home-wear, a smoking jacket and a dressing gown. English, ca. 1873, Courtesy Victoria & Albert Museum CC BY NC

The beginning of the nineteenth century has been appointed as the period of the so-called ‘Great Masculine Renunciation’. Even if greatly problematic, this definition is useful to understand the higher degree of separation between private and public spaces, and the different frames of consumption of these spheres. In this period, the adoption of the three-piece suit in plain colours for public life is opposed by a freer consumption of fashion inside domestic spaces. While conforming to the fashionable cut of popular redingotes, banyans kept being made in colourful and rich textiles, either velvets, printed silks or cottons, demonstrating the underlying need for men to experiment with prints and textures.

Banyan and waistcoat made from a Chinese dragon robe, Italian, 1780-1810, Courtesy Victoria & Albert Museum CC BY NC

Instead of talking about a ‘renunciation’, it is more suitable to talk about a move to a subtler way of experiencing fashion, both in the shaping of the self and in the social performance, that was to delineate a new masculinity. Even home is then a place in which to negotiate an identity in definition, responding to growing anxieties coming from the outer world. Banyans, in their construction and design, speak of a changing relationship between identity and appearance, conveyed by the shape of the body, which had to be effortlessly perfect in every place and at every degree of privacy.

Europeana Fashion Focus: Sweater by Walter Van Beirendonck, 1987

This sweater in knitted wool was designed by Belgian fashion designer Walter Van Beirendonck for his ‘Dare Devil Daddy’ A/W 1987-88 collection. Its trompe l’oeil design reminds of the typical look of the ‘strongest man on earth’ character from twentieth century freak shows.

The Marinière, a Parodic Parader

In 1983, Jean-Paul Gaultier debuted his first ready to wear menswear collection. Entitled ‘L’Homme Objet’. The collection featured the designer’s own take on the ‘marinière’, the French seaman shirt, which soon became an essential element of his design grammar.

THE EDITOR’S COLUMN: UNIFORM(S)

This month the Europeana Fashion Blog dedicates its entries to the many forms and definition of ‘uniform’, reflecting on the intricate relationship fashion establishes with power, representation, identity.

‘Rik Wouters & The Private Utopia’ on Europeana Fashion Tumblr

MoMu is the new curator of Europeana Fashion Tumblr. This September, in concurrence with the museum’s latest exhibition ‘Rik Wouters & The Private Utopia’, the Europeana Fashion Tumblr page will showcase pictures and artworks unveiling the themes of the exhibition.