Archive for November, 2016

THE EDITOR’S COLUMN: GALA

December is, by definition, a festive month. The many celebrations crowding our calendars during the last month of the year call, necessarily, for the right dress. For this month’s theme, we decided to dive into the Europeana Fashion archive and pick the best objects representing December’s party mood, concentrating around the idea of ‘Gala’, and its translation into clothes and accessories.

Fashion plate, showing an evening dress and ball dress, from 'La Belle Assemblée’, 1828, Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum CC BY

Galas are part of popular imagination as dreamlike events, where everything – from the little details to the actual design of the whole experience – concurs in the defition of the uniqueness of the moment. The architecture of these moments is as ephemeral as it is marvellous, and it it in their being rare and, most of the times, of restricted access that events such as galas, balls, and other social performances catch people’s fantasies, provoke admiration and desire.

Evening wrap of silk taffeta, probably made in France, 1904, Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum CC BY

Galas have been portrayed in stories and fairytales as pivotal moments in the articulation of the narrative, and in these cases artefacts are most of the times the core devices to visualise the importance and relevance of the event: one for all, the power of Cinderella’s shoe in making the story iconic in itself. This idea has been taken up into the transposition of these stories into movies, where costume designers have the task to make garments speak.

Embroidered Evening Gown designed by Vionnet, 1929, Courtesy Les Arts Décoratifs Paris, All rights Reserved

Apart from showcasing some material examples relating to special occasions, we will look at the people who are responsible of making the ‘stuff’ of which these dreams are made of: designers, but also embroidered and manufacturers responsible of the various objects populating these gilded scenarios. Some space will be dedicated to the ‘master of ceremonies’ and their role into contracting and disseminating this desire.

So, await for some fascinating insights on the material culture of partying and gala and, please, dress accordingly.

Wide and strong: shoulder pads

‘To have broad shoulders’ is a quite common idiom, meaning ‘to be able to cope with difficult situations’. As it often happens, the metaphorical meaning of the sentence is directly linked to the image it evokes; and fashion, with its ability to act on the shape of the body, has proved to have much to do with the construction of this visual metaphor.

Dress designed by Elsa Schiaparelli, 1946, Courtesy Galleria del Costume di Palazzo Pitti, All Rights Reserved

Although it is difficult to pin down the period in which pads for shoulders came into use – padding was something that has been quite often used in costume, for any part of the body – the shoulder pads we are familiar with are quite recent. They were in fact popularised in the 1930s, by designers such as Elsa Schiaparelli and costume designer Adrian, who dressed Joan Crawford in her iconic movie Letty Lynton. The silhouette of the 1930s reminded of a triangle with the basis on top: so, in very simple visualisation, wide shoulder line e very narrow pencil skirts.

In terms of materiality, shoulder pads were originally semicircular pieces of cloth stuffed with different materials, from cotton to wool or sawdust. With the outburst of the war in 1939, feminine fashion followed a period of ‘militarisation’: jackets had to represent severity and solidity, and the shoulder, constructed by bulky pads supporting their ‘hard’ shape, seem to metaphorically bear the burned of those hard times. Even though after the war the shape of the silhouette in vogue changed completely, shoulder pads were still in use, though in smaller size, to graciously perfect the line of dresses and jackets.

Ensemble designed by Gianni Versace for his Winter Collection 1983-1984, Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum CC BY

A decade that saw the revival of shoulder pads is that of 1980. Shoulder pads were used by designers reflecting on the link between women and power, and used them in the definition of what is now commonly known as ‘power dressing’: a sort of uniform for the up-and-coming, hard-working women that in those years were battling for equal opportunities within the working environment. Maybe because they remind an armour, big shoulders still recall a sort of strength and are associated with self confidence and power.

Interestingly, shoulder pads became also a feature of attires used in performances by musicians and artists, who also tended to wear jackets with heavy decorations on the shoulders so flashy to caught attention, often becoming the epicentre of the entire look. This is true for the 1980s, but also today: many ‘big-shoulders’ look are considered statement, above all when worn by female performers whose feminist activism lays primarily in their costume choices.

Europeana Fashion Focus: Housecoat by Paul Poiret, 1923

Housecoat, Paul Poiret, fabric Atelier Martine, 1923. Courtesy Modemuseum Hasselt, all rights reserved.

The housecoat for man is made of cotton velvet, printed with a floral pattern in multiple colours. It was designed by Paul Poiret in 1923, and made using the fabric produced by the Atelier Martine, the designer’s atelier dedicated to interior and textile design.

The coat, reminiscent of the eighteenth-century banyan, has a straight line, extended shoulders width and low, kimono-like, sleeves. The wrap over neckline is embellished with a wide collar. A belt is used to tie the coat on the waist. Right under the waistline, two patch pockets are attached.

Interested in the works produced in the Wiener Werkstätte, Paul Poiret opened ‘Martine’ in 1911. He named it after one of his daughters; it consisted of École Martine, Atelier Martine and La Maison Martine. The École Martine was an experimental school for working-girls directed by Marguerite Gabriel-Claude Sérusier, where the students applied themselves to sketching plants and animals at parks and zoos. The best drawings were bought by Paul Poiret and printed on the textiles and wallpapers that were produced by the Atelier Martine. The atelier was very avant-garde in terms of motifs and production, and also featured collaborations with Raoul Dufy. Eventually, Poiret sold ‘Martine’ enterprise in 1925.

The object is part of Modemuseum Hasselt. Discover more on the Europeana Fashion Portal.

The Maxi Dress

The Maxi Dress appeared in the 1960s, launched by high-end fashion designer Oscar de la Renta, already famous for his women’s evening wear and suits.

By 1968, when the New York Times published a lacy cotton version made for Elizabeth Arden, millions of people started buying and wearing dresses designed alongside the lines of this famous one; the Maxi Dress then became a women’s wardrobe essential throughout the 1970s. The popularity of this model is also due to the costumes designed for the movie based on Pasternak’s book Dr. Zhivago, in which Julie Christie wore flowing romantic maxi dresses, as well as maxi coats over trousers.

The most common maxi dresses were initially slightly shorter than ankle length, and usually made of lace. It wasn’t until the 1970s – the decade in which it gaind huge popularity and became a must-have fashion item, along with similar caftan and boho-styled clothing – that it started being decorated with a wide variety of motifs, from paisley to exotic and psychedelic prints. Designers such as Yves Saint Laurent, Biba, Halston, Ossie Clark and Pierre Cardin came out with their own stunning versions of the trend.

This peculiar design, almost completely disappeared by the 1980s and the 1990s, has recently made its comeback; today in fact, the maxi dress has become a go-to-garment for women all over the world, since its form can be adapted according to different requirements, either of style and substance.

Wide Stories: The Mantua

Popular for what we now consider an exaggerated silhouette, the ‘mantua’ – a style of gown in fashion in the late seventeenth century and early eighteenth century – bears a story as wide as its volumes.

Introduced in Europe in the 1670s, the mantua was in origin a loose coat for women, with a kimono-like cut. It was inspired by the clothes and robes recently imported from India, that were worn by Western men as dressing gowns.

The name ‘mantua’ might refer to the Italian city of Mantova, once an important centre for the production of exquisite fabrics; or, it might be an evolution of the French term ‘manteu’, which referred to nightgowns and dressing gowns. The latter explanation makes sense, given the fact that it was worn as a kind of ‘undress’, as its earliest one-piece structure was free of the stiff boned bodice of the ‘grand habit’ that was in use in the court.

Though simple in its construction, the preciousness of mantuas reflected that of the fabric of which they were made, which was usually a kind of silk damasks now known as ‘bizarre silk’, fashionable in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century. The ‘mantua-making’ was a women’s trade, as millinery was, and was officially recognized in France as the first guild controlled by women.

Mantua and petticoat of French silk, brocaded with silver-gilt threads, made in England, 1755-60 of French silk, 1753-55. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, CC BY.

Initially considered too informal to be worn outside private spaces by Louis XIV, by the end of the 17th century the mantua became the formal dress worn in the courts of Europe and continued to be worn in England until 1820, when George IV suggested it should be abandoned. As in the early eighteenth century elliptical side hoops came to fashion, the shapes of the mantua changed to accommodate them. Following the crazes of the court, its width even reached, in the most extreme cases, two meters.

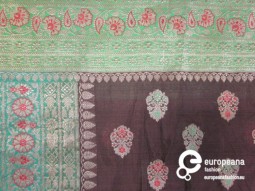

The fabric of desire: indian textiles

Objects from different, often unknown cultures have for so long cast a spell on the imagination of people in the West. Geographical distances weigh on the ‘cultural capital’ of artefacts that come from far away. Then, if these objects are something so unique they can be hardly reproduced at home, their material value combines with the meaning they acquire when they travel, in space but also in time.

Indian textiles have been leading the global trade for long, from at least the seventeen and eighteenth century, when huge amounts of indian cotton started to be brought to Europe because of their quality and price. Till at least the eighteenth century, Indian textiles were technically much more advanced than the ones produced in Europe, and were therefore generating desire among the fashionable consumers, who were seeking to distinguish themselves by owning something as precious and finely made.

Embroidered cotton dress, with textile probably coming from Gujarat, 1780, Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum CC BY

Indian textiles can be classified according to the region of production or the technology implied in their making, as different techniques have been developed within the different Indian districts. Threads made of cotton, silk, wool and even gold and silver were used to embroider on different materials, from the most ‘common’ – silk, wool and of course cotton – to less expected ones, such as velvet and leather. Many decorations are implied in the production of these textiles: small mirrors, shells, coins, gems and sequins are all used in different ways, also testifying the skill and craftmanship of the producers.

Indian textiles are known for the vivid colours, given the special natural dyes used, but what really attracted western consumers are the exotic motifs and unique decorations such as the ones these fabrics showed in their embroidery. For example, one of the most interesting embroidery technique is the Zardozi. It is done on different fabrics: silk or velvet are the most common,embellished with either chain stitch, stem stitch or satin stitch. The embroidery is made with some so-called ‘zari’ threads and different kind of threads, which can be twisted, untwisted and also metallic.

Rajput wedding gown made of silk, embroidered with zardozi technique, Courtesy Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, All Rights Reserved

Another embroidery technique is the Gujarat, whose typical motifs are flowers, plants and animas, but also human figures can be found on these kind of textiles. The embroidery is done with multi-coloured threads, usually in cotton or silk. Different stitches are used depending on the style of the figures: chain stitch, herringbone stitch, satin stitch, interlace stitch, buttonhole stitch and darning stitch. Mirrors are also used to embellish the whole pattern, which can be made of forms made of scraps of other fabrics stitched on top of the basis.

Visit the Europeana Fashion portal to virtually travel to India and get fascinated by these amazing items.

From a Doll’s Wardrobe: Maison Martin Margiela A/W 1994-95

In the autumn/winter 1994-95 women’s prêt-à-porter collection designed by Maison Martin Margiela, some clothes showed unusual features. These items all reported a second label, which stated: ‘Garments reproduced from a doll’s wardrobe (details and disproportions are reproduced in the enlargements)’.

Dolls and fashion have tight connections. If in recent times dolls are associated with the particular image of the sassy fashionista, in the past they have been an important method of communication and reproduction of fashion. Their minute dimensions were an advantage for couturiers and textile producers, since they could use them to present their creations to a broader public with a moderate use of fabric and limited shipping expenses.

However, their minute dimensions also represented a limit, for accessories and cuts couldn’t be reproduced in exact proportion. Looking at the clothes designed for popular dolls like Barbie, Ken and G.I. JOE, Maison Martin Margiela focused on these peculiarities, as the zippers and buttons, pockets, un-anatomic cuts and unfinished details and up-scaled them to life size, making this disproportions more evident.

Though playful in his approach, with this overturn Maison Martin Margiela explored the concept of the standardised body, highlighting its contractions and conventions, as magnified in the idealized and un-realistic features of the toy dolls; the collection also reflected on how both the female and male bodies are keen to undergo this process of standardisation by fashion and social ideals.

Sweater, Maison Martin Margiela, s/s 1999. Courtesy MoMu - ModeMuseum Provincie Antwerpen, all rights reserved.

In the collection, odd details as oversized accessories, un-attached collars and seams left with uncut threads contributed to the atmosphere of ‘unease’ that was associated to the mystique of the Maison. Sticking to the overarching project, the knitwear pieces of the collection were even realized with a thicker thread, accordingly to the false proportions of the toys’ clothes. The Maison also reprised this theme for the spring/summer 1999 menswear prêt-à-porter line, which featured coats with faux oversized front buttons, chunk zippers and and huge ID tag chains.

Find more pictures from this and other Maison Martin Margiela collections in the Europeana Fashion portal and learn more about Barbies and dolls in fashion exploring related entries our blog.

Megastructures

The way in which the feminine figure has been more widely represented focuses on the exaggeration of the feminine characteristics; example of this are the so-called ‘Venus’ Figurines, statuettes of women created in the upper Palaeolithic.

Whether representing a sensual meaning or an invocation of fertility, the general similarity in design and shape of these sculptures is extraordinary. All of them have a wide belly tapering to the head and legs, and their abdomen, hips, breasts, thighs, vulva are often deliberately exaggerated. Despite the ongoing debate regarding their cultural significance, they offer a possible understanding of the iconic role of females in the Stone Age communities.

Exhibition "Correspondences" by Yohji Yamamoto. Pitti Uomo 67, 2005. Photo by Alessandro Ciampi. Courtesy of Pitti Immagine. All rights reserved

In fashion and clothing, the image of the large and flourishing hips has been transferred in the forms and shapes of the full skirt. Numerous techniques have been used throughout fashion history to extend the circumference of this female garment, including the farthingale in the sixteenth century, hoops in the eighteenth century and, in the nineteenth century, the crinoline. This set the ‘hourglass silhouette’ as peculiar of femininity, whose shape is still considered the ideal shape of a woman’s body, recalled in fairytales and in the most traditional model of wedding dresses.

Ball gown for Lady Lamington consisting of a full crinoline skirt with puffed panniers designed by Madame Handley-Seymour. London, 1938. Courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum. ©Elizabeth Handley-Seymour CC BY

Historical periods, life conditions and social status have influenced exaggeration in women garments too, as the lavish and luxurious confections made by the couturier Charles Frederick Worth during the regime of Napoleon III from 1852 to 1870. His international reputation for clothing the fashionable elite came to represent the opulence of the “Golden Age”, an era of material prosperity.

The attempt to reprise the crinoline and design the woman body with the silhouette of the dress in order to make it overlapping the ideal reemerged with Christian Dior’s New Look in 1947. One of his bestselling items was the Bar ensemble, a two-piece suit that exemplified the exaggeratedly female silhouette by means of a rigid infrastructure of wire, whalebone and cambric that imposed an independent sculptural form over the natural lines of the body.

Model Jac on catwalk wearing a dress for Viktor & Rolf . Autumn-Winter 2010, Womenswear Collection. Courtesy of Catwalkpictures. All rights reserved

Contemporary avant-garde designers continue to play with proportions and structures in their collections; Vivienne Westwood’s “Mini Crini” collections of 1985 and 1987 and the extreme silhouettes, opulent fabric and lavish trimmings of John Galliano are two example of contemporary use of crinoline. In the most recent use of structures in fashion an estrangement from the sensual meaning stands out in favor of a gathering between fashion, contemporary art and architecture, as in the work of Comme de Garcons’ designer Rei Kawakubo, who constructed structures in crinoline outside her garments or in that of Viktor&Rolf, whose collections on catwalk bear resemblance to performances of contemporary art.

(Small) objects of desire: Réticules and Minaudières

Nowadays, it is difficult to imagine a woman, whatever her taste, role or occupation, without a bag. Bags allow to carry all the things we need – and want – to keep with us. In their most iconic versions, they can even be considered a statement on their own right. Interestingly, late eighteenth century popular bags were so small they were considered ephemeral, nearly a ‘joke’.

By the late 18th century, the line of women’s clothing changed: skirt and dresses were clinging to the body, the overall silhouette very fitted and the materials used were more lightweight; for these reasons, pockets were difficult to be added to patterns. Therefore women began carrying small, drawstring satchels or purses, often made of silk net, similar to the bags used to carry their needlework, but considerably smaller. These bags were used to carry a perfume, face powder, handkerchiefs, and all their portable ’beauty tools’.

The term used to indicate these objects was Réticules, often mangled in Ridicules: the former refers to their appearance, whilst the second is clearly liked to their small size. Irish traveller Katherine Wilmot defined Réticules in an entry on her diary dated 1801 as ‘species of little Workbag worn by the Ladies, containing snuff-boxes, Billet-doux, Purses, Handkerchiefs, Fans, Prayer-Books, Bon-Bons, Visiting tickets.’ Reticule comes intact from the Latin reticulum, which means ‘small net’, while Ridicule recalls the French for ‘funny’ or even ‘pointless’.

Even if considered useless by some commentators - the idea of women carrying their private objects was ‘ridiculous’ in itself - these items were quickly to become a fundamental feature of women’s attire: their popularity improved and their design developed. Réticules often were coordinated with the outfit and makers experimented with different materials and motifs. By the mid 1800’s, the style changed: the most popular was the flat style, that could be made different shapes, either round or squared, and were generally fastened with a metal fastener, which was both functional and decorative.

Another example of bag characterised by its small size is the minaudière. This particular object, which stands in between the bag and the jewel, was invented – and patented, in order to avoid copies – by Van Clef & Arpels in 1934. It is said that Charles Arpels was inspired by socialite Florence Gould, who used to put her makeup items into a tin box. Minaudière were deemed ‘essential’ by many accounts during the 1930s and 1940s. Although being valued mostly for its ‘outside’, In the original version the minaudière was a carefully designed item above all in the inside: small compartments were arranged, in order for women to be able to carry all the small items a social night requested.

The Europeana Fashion collection holds numerous of these ‘essential jokes’ from different periods and places: explore the archive to know more.

Europeana Fashion Focus: “Nodini” Sandal by Salvatore Ferragamo,1939.

The “Nodini” Sandal is made of cellophane and wicker, in the shades of blue and yellow. It belongs to the 1939 summer collection designed by Salvatore Ferragamo and represents one of the first models of shoes realized with that material.

The sandal is composed by a framework of cellophane on a blue wicker bottom, decorated with ocher knots. It has an ankle fastening and a wood heel covered by black kidskin.

Salvatore Ferragamo told that his biggest problem during the war was to find a material to replace high quality kidskin leather. One day, after many attempts, he found a solution in a chocolate box that was given as a gift to his mother : when unwrapping one of the chocolates, he was impressed by the material and thought it could be what he was looking for. Since then, Ferragamo started to make shoes in cellophane for his summer collections.

The object is part of Museo Salvatore Ferragamo. Discover more on the Europeana Fashion Portal.