BlogRSS

Sportswear. Shaping the American Look

In the Thirties, a group of American fashion designers turned to sportswear to meet the needs of the modern American woman. Their easy, utilitarian looks, far from those of the French couture, gave new shape to the American look.

Museo Salvatore Ferragamo curates the Europeana Fashion Tumblr this month!

Museo Salvatore Ferragamo discloses the contents of its current exhibition ‘Across Art and Fashion’ on Europeana Fashion Tumblr, exploring the relationship between artists and fashion designers!

The concept of the exhibition draws directly from the life story of Salvatore Ferragamo, whose fascination with twentieth century avant-garde art movements led him to seek for inspiration in the art world. It presents various case studies, analysing the ways in which these two worlds have interacted, through contamination, overlap and collaboration.

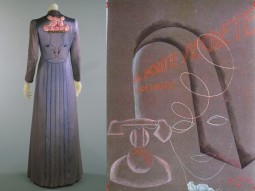

Maison Vionnet, ‘L’Orage’ model, 1922, dress in taffeta, inlaid with rectangular motifs in a geometric progression. Collection Musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris. Thayaht (Ernesto Michahelles), Madeleine Vionnet, Manifesto, 1919-23, colour lithograph on cardboard. Collection Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli, Bologna. Courtesy of Museo Salvatore Ferragamo. All Rights Reserved

The exhibition includes a rich catalogue of clothing, accessories, fabrics, works of art, books, periodicals and photographic material from Italian and international museums and private and public collections that will surprise you; from the Salvatore Ferragamo’s pumps, inspired by the work of American artist Kenneth Noland in the Fifties, to the installation of photographs by Andy Warhol, Altered Images, and generous loans from Studio Makos and Keith Haring’s Fertility, and much more.

Elsa Schiaparelli with Jean Cocteau, Evening coat, Autumn 1937 collection, knit rayon. The Rubin cup motif, designed by Jean Cocteau, was embroidered by the Maison Lesage. Collection Philadelphia Museum of Art. Jean Cocteau, La Porte Secrete, c. 1933-4, mixed media on cardboard. Collection Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli, Bologna. Courtesy of Museo Salvatore Ferragamo. All Rights Reserved

The aim of this unique exhibition will be well represented in the Tumblr curation, which will feature everyday artworks and the dresses they inspired, following the same outline of the display on show. The curation has been possible thanks to the close collaboration between Europeana Fashion with Museo Salvatore Ferragamo, supporting member of the project since its very beginning.

Visit Europeana Fashion Tumblr everyday to find new amazing images. Read more about the exhibition “Across Art and Fashion” on our blog and find on Instagram the pictures of our visit to the exhibition at Museo Salvatore Ferragamo.

THE EDITOR’S COLUMN: Leisure

In line with the much awaited arrival of August, this month’s theme for the Europeana Fashion Blog will be Leisure, in its many forms and definitions.

Sociologist Thorstein Veblen has defined leisure as the non-productive consumption of time. In being directly related to acts of consumption, leisure has called for a whole set of goods and situations precisely designed to produce leisure time, and make it productive.

Designing for leisure means, once again, to design a well-defined lifestyle, made of various activities and very precise looks linked to the occasion they are thought to ‘fit in’. Amongst the activities connected to the idea of ‘free’ time – even though the concept is in itself rather diverse – two are the most direct: sport and travel.

Sports act on the very form of the body, and since the goal is a good performance, both the body and the clothes have to serve this purpose; many designers have bounded their name to one or more sport activities, applying a method that is different from that of couture. In sport, ‘function over form should’ be the norm, but this idea has been overturned by designers themselves, who have often played with the stereotype – and won. The ‘use’ of sport as a motif for fashion design has even historically led to the differentiation of a ‘national’ fashion – most notably the patriotic american fashion of the 1930s, which sought to emancipate from paris by concentrating on leisure-wear.

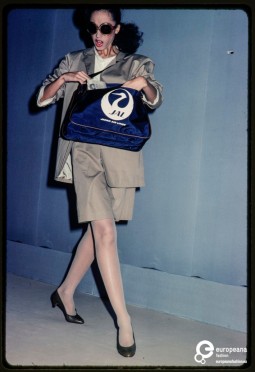

Kenzo, spring-summer 1982 women's rtw fashion show at the Jardin d'Acclimatation, Borte des Sablons, Bois de Boulogne, photo courtesy Paul Van Riel

From a very patriotic act to the will to enlarge views and know other places, travel holds a special place in the world of leisure. ‘Travel time’ in itself may not be considered leisure, but it is still a ‘suspended’ moment of transfer that was exploited by creators, who made it a fashionable event in its own right; and clothes as well, in their very design, can represent a journey, recalling, with the inspirations they hold in their construction and decorations, places and memories – real or just dreamt.

Leisure as a concept has become more and more democratic as the times have changed the social structure Veblen based his writings on, and more precisely its diversification played a major role in the definition of new social groups. In fashion, leisure-wear is a wide and quite muddy concept that gathers many different sectors of the fashion system. Each activity is analysed and, in some ways, celebrated with dedicated events, publications and other ephemera. This month the Europeana Fashion Blog will unveil some of these materials and tell their stories: stay tuned.

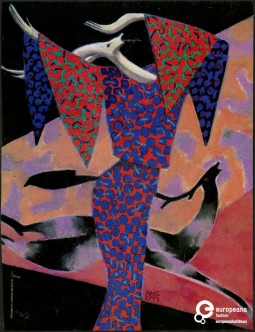

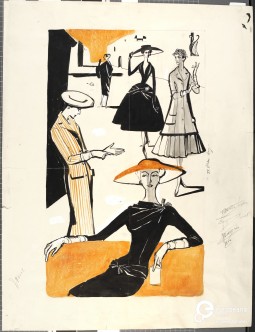

Lorenzo Mattotti

Illustrating fashion is a very peculiar act; while sketching is the earliest stage of the design process, when the idea gets the form of some lines on a sheet, fashion illustration calls for a completely different context and then, a different meaning. It is about retracing the idea behind a real dress, imagining a set and visually writing a story.

It is not necessary to come from inside the fashion world to be able to capture the intrinsic nature of fashion; Lorenzo Mattotti exemplifies the fact that what is needed is instead a good eye and an open mind. Mattotti started to illustrate fashion when the ‘Valvoline’ group, a collective of comics illustrators founded between 1982 and 1983 with, as members, Igor Tuveri (Igort), Giorgio Carpinteri, Marcello Jori, Jerry Kramsky, Daniele Brolli, Charles Burnes e Massimo Iosa Ghini, started participating to the pages of Vanity, the avant-garde illustrated fashion and style magazine founded by Anna Piaggi at the beginning of the 1980s.

Of the whole group, he is the one who has established the longest relationship with fashion; this, probably because it allowed him to explore some themes – above all the relationship between identity and performance – that are central for him as artist and for the mythologisation of fashion itself. He has recently declared, in an interview to the Newyorker: “Doing fashion illustrations is part of my work, but for me it’s all about women. When I look back at my work, I see images of women. It’s all about women—very pictorial women putting on dresses, putting on a show.”

Mattotti’s provenance from the world of comics shows in his approach to the actual clothes in the illustrations made for fashion. Clothes are, for him, a pretext to reflect on the formal composition of images, and on the possibility to build narratives around the encounter of a body, a personality and a dress. The worlds he portrays do not want to be true-to-life, nor his personnages are immediately recognisable as ‘humans’, as it is clear in the illustration made in 1985 for Vanity, featuring Missoni clothes.

His interest in the body and its materiality goes together with the necessity to portray the materiality of clothes and textiles. All his works show his great attention to prints, embroideries and textures, together with his will to place clothes in an imaginary setting, establishing interesting links between what is visible and what is imagined, between reality and utopia.

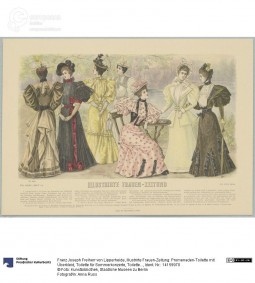

Lipperheide Costume Library

Both an international research library and the world’s largest museum collection of graphic works on the history of clothing and fashion, the Lipperheide Costume Library constitutes a milestone for fashion research.

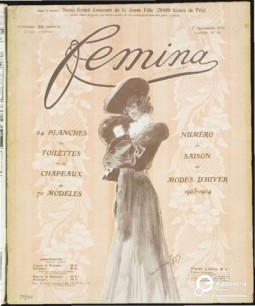

Femina

Subtitled ‘The perfect review for women and girls’, the illustrated magazine created on 1st February 1901 by Pierre Lafitte took its name from the Latin word femina, meaning ‘woman’.

Femina was the first French magazine targeting a female audience, consisting mainly of readers belonging to the middle class; central for the magazine was the support to Parisian fashion in the early twientieth century, which was advertised thorugh the pages as the most fashionable option for intelligent and refined women caring about their appearance.

The illustrations represented the main attraction of the magazine. On May 1st, 1903, Femina titled “Women Artists at the 1903 Salon” and dedicated three pages to the illustrations of Louise Abbéma, Louise Catherine Breslau, Camille Claudel, Maximilienne Guyon Louise Clément-Carpeaux, Laure Coutan-Montorgueil and Juana Romani. After a few years, the magazine cover, which had previously been mostly a reproduction of a photograph, started to be accompanied by a cartoon illustration in bi-chroma.

Anne R. Epstein, in her review of the book by Colette Cosnier, The Ladies of Femina, described a mystified feminism in the editorial direction of the magazine. Indeed, Femina was not born to be a feminist magazine but rather a woman’s magazine. The editorial strategy of Pierre Lafitte, the publishing director, was inspired by The Ladies’ Magazine, a successful English publication.

He envisioned a luxury magazine dealing with fashion trends, society and family. However, feminist topics of the time – including the claims of the suffragettes in England and the acquisition of voting right by the Danish women – were treated and discussed in the journal. Moreover, Lafitte used to give great prominence to leisure and sports in practiced by women and, from 1906, he launched The Femina Cup, a sporting competition.

In 1909, the French Academy raised the question of the election of female members: immediately Femina asked its readers to elect 40 writers, to fill an imaginary female academy and published on a double-page an illustration showing the 40 elected seats in the institution’s dome. After being suspended in 1917, Pierre Lafitte sold the journal to Hachette; the publishing house then merged Femina with another magazine called “The Happy Life”.

Visit Europeana Fashion portal to see more Femina’s images from our archive.

Europeana Fashion Focus: ‘Évêque’ ensemble, designed by Paul Poiret, 1907

The outfit is a summer ensemble composed by a dress and a bodice. The dress is made in linen and cretonne; it was designed in 1907 by french couturier Paul Poiret. The french word ‘évêque’ means ‘bishop', recalling the proportions and overall look of the cassock used by members of the clergy.

Constance Wibaut

The Dutch fashion illustrator Constance Wibaut (1920 - 2014) once said that the hardest part in fashion drawing is ‘how to get chic on paper’.

Parades: Identity on display

Parades are celebrations filling the streets of a city with people marching together, for the most various reasons. They are highly designed events, in which costumes play a fundamental part in defining the tone and overall image of the celebration itself.

Parade with local costumes from Messologhi, Greece, 1936-1939. Courtesy Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation

Parades, above all official or military ones, represent the encounter with the necessity to give a ‘face’ to power and the interest in using the ‘spectacle’ to produce consent. For this reason, from the parades originated various ‘bidimensional’ materials that had the role of portraying an ephemeral performance, to record and remember it; these materials are what we use today to know more about these performances. In fact, the most direct and immediate source to get to know something about parades of the past are prints and, where possible, photographs; these materials, together with actual garments and props that survived in museum collections and archives, are for us documents of past practices and also fascinating postcards showing the different ways in which people used to colonise the streets of their city and shape their common national or group identity.

Tinted photo of men with costume from Pontus and a man with military uniform. Courtesy Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation

Even though it is excessive to say that parades can be read as quasi-fashion events, the similarities are hardly deniable. They are both highly controlled, from the timing and choreography to the dresses and walk, and serve to present something, be it a collection or a set of military values, and convey meaning. Fashion historian Caroline Evans has underlined the common features between the first fashion shows held at the beginning of twentieth century and military parades, highlighting the link between the two events, in which dress is central. The design of parade attires is very precise, and each detail has a role in producing the spectacularity of the march: the factors taken into account were multiple, from the sound of medals in movement, to the dimensions and look of accessories and insigna, to the effect of light on the different colours and textures.

Plates depicting uniforms and ‘parade attires’ are very important, not only to understand how the outfit were composed and what details differentiate roles and positions; they also give us information about the way each garment had to be styled and what kind of pose and ‘posture’ they requested, in order to perform in a successful way.

March to our collection and seek new stories about fashion and uniforms on the Europeana Fashion portal.

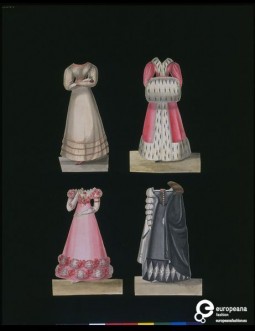

The Paper dolls of Anne Sanders Wilson

Printed or hand drawn, paper dolls were widely used throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as toys for children, or as a funny entertainment for wealthy adults.