BlogRSS

Modest and Practical: Dressed to Travel

Since travelling became an accessible activity in the nineteenth century, travellers have been in search for a special attire designed to accompany them on their fares, eventually promoting new trends and customs.

The Sailor Suit: history and Influences

The sailor suit, as a fashion trend, begun in the Victorian Age, developing at first as a children costume phenomenon; worn as school uniform and then for sport performances, it has kept its popularity until today.

Like many naval-inspired designs, the sailor suit originated with the British navy and was then copied into other navies. The uniform, in its most traditional form, was worn by enlisted seamen in the navy and other government funded sea services. It is also known as “Number One” uniform, its first use is for ceremony, taking this name from the old working rigs of Royal Navy sailors. Since its first introduction in 1857, it has changed continuously, to adapt to the costume evolutions of each period, but always keeping some details, and precisely the blue jean collar, as its most recognisable items.

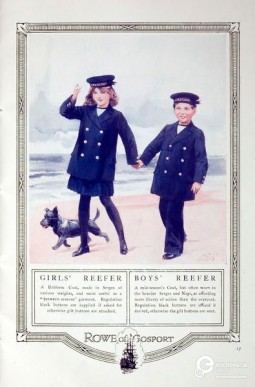

"The Royal Navy of England and the Story of the Sailor Suit" Trade pamphlet on children's garments issued by Wm Rowe of Gosport, Cowes & London. England, ca. 1900. Printed paper. Courtesy of Victoria and Albert museum. CC BY SA

It was the 1846, when Queen Victoria was delighted, during a cruise off the Channel Islands, by seeing her four-year-old son Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, wearing a scaled-down version of the sailor suit of the Royal British Navy. His portrait was painted at the same time, right when the British Navy was the most powerful naval force in the world and its uniform had recently been standardized. So the portrait, as well as a series of engravings, made the sailor suit became popular among the British public; later it was introduced as a normal dress for both boys and girls all over the world, with some variations through different nations, according to the specific naval uniform of each country.

The sailor suit became the first popular children’s fashion trend by the 1880s, when advertisers began marketing it. For boys it consisted in a middy top with shorts or long trousers, replaced by a skirt in the feminine version. The two models had in common typical marine designs as stars, anchors or eagles, sewn on as badges. Ready-made or sewn at home, they closely resembled actual naval uniforms and used to change togheter with the development of the official ones. They were usually made of washable, sturdy fabrics like wool serge and allowed relative freedom of movement. Probably depending on this, sailor suits have soon been adopted for a variety of social situations, helping to strip away the class distinctions, a prominent aspect of British culture. Also sailor suits were frequently worn as school uniforms, probably due to their military origins and to an association with order and discipline.

Born as a thought-for-men ensemble, the sailor suit has anyway influenced women’s style in more than one way. In May 1904, Harper’s Bazaar called a sailor suit ‘the most serviceable all-around frock a girl can have’; a female version of the sailor suit, the sailor dress, was popularly known in early 20th century America. Since then, women’s fashion picked it up as casual seaside wear and it became associated with sport, summer and leisure. Elements of nautical style were absorbed into adult dress, including blue and white stripes, square sailor collars and wide, loose trousers, which are enduring elements of spring and summer dress.

Discover more sailor suits on the Europeana Fashion portal and follow @Europeanafashionofficial on Instagram to discover the sailor suit’s curation of this week!

I See Red: Fox Hunting Attire

The value of tradition in sport is linked not so much to the performance in itself - improved by new techniques and exercises, pushing the limits of body and mind - but, more often, to the presentation of both the athletes and the event as a whole. Then, the sportive act becomes a ritual, in which the form is valued as highly as the substance, and whose presentation ends to develop into a custom.

Europeana Fashion Focus: Evening Ensemble by Germana Marucelli, 1968

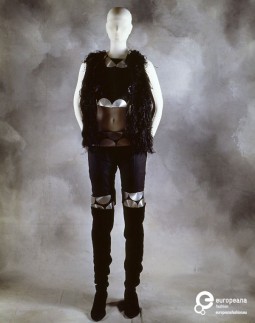

The outfit is an evening ensemble composed by a bodice, a waistcoat, a pair of shorts and boots. It belongs to the 'Linea Alluminio', Alta Moda collection for the Autumn/Winter 1968/9. The ensemble, embellished with anodized aluminium elements, was designed by Germana Marucelli and realized in collaboration with the artist Getulio Alviani.

To dress à-la-plage: Designers and Resorts

As early as it became popular to travel to fashionable seaside resorts, fashion designers and couturiers found their way in dictating the trends by the sea, not without being moved by the different landscapes and lifestyles.

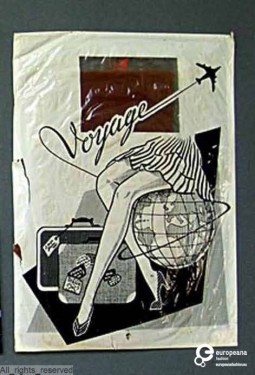

Luggage: a travel through history!

Even in the quite small time of its 120-year history, the development of luggages is surprisingly articulate and full of implications with the improvement of the social lifestyle. Starting from the steamer trunks of bygone eras to the sticker-covered, double-locking suitcases of the 1950s and ’60s and

On Cities on Clothes: Moschino ‘Cruise me Baby’ collections

Cities hold a pivotal role in the fashion system. Not only because of their position as catalysts in the production, promotion and distribution of fashion; also, in their being the places where fashion, as a social phenomenon, blossoms, being shaped by the identity of the city itself and by that of its Inhabitants.

The specificities of each city allow to consider its active role in the creative process, and most of the times the stereotype becomes the basis on which to work in order to reinvent itself without forgetting the roots. The central importance of the city, as a set of special features and history, is clear in the words of the storyteller as well as in the mind of the image-maker, who builds an aesthetic on the glimpses and perspectives that can be encountered while wandering around.

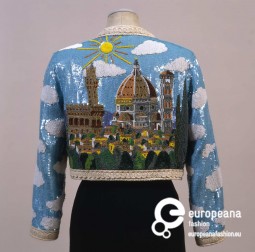

Jacket from Moschino 'Cruise me Baby' collection, S/S 1993, Courtesy Galleria del Costume di Palazzo Pitti

Sometimes, cities are de-materialised – and then re-materialised again – during the creative process, and end to become messages inscribed on the clothes. Many are the designers who used cities on their clothes, rethinking them as embroideries, prints, patterns; the cities used to ‘inspire’ the designs are never chosen without a real reason: most of the times, it is for the kind of atmosphere they evoke, and for the bond the designer has with that particular place. This is what happened with Moschino and the ‘Cruise me Baby’ collections of the first half of the 1990s.

Moschino launched its ‘Cruise me Baby’ line at the beginning of the 1990s. Between 1991 and 1994, the collections were dedicated to some of the most important Italian cities; Naples, Venice, Florence, Pisa and Rome became flat patterns, or were sublimated in symbols to ornate jackets, waistcoats, shirts and dresses; Florence, for instance, was both represented as a landscape, displaying the sublime architecture of the city and its amazing panorama, and as sign, the lily, historical symbol of the city, multiplied as a quasi-geometric pattern, next to black and white squares and dreamy clouds.

Jacket from Moschino 'Cruise me Baby' collection, S/S 1993, Courtesy Galleria del Costume di Palazzo Pitti

The style of the collections was true to the identity of the brand: a familiar cheekiness, refined in its being overtly tacky. The designs were also a love letter to Italy, celebrating the many faces of a Country that made of its regional diversities its strength, playing on the differences to build a varied international recognisability.

The clothes Moschino designed can be considered like postcards: they can be seen as patriotic banners to be preserved and showcased, or they can be a more intimate object, whose material qualities can hold memories and recall sensations. In both ways, the city itself becomes the message, and the use of the object comes after the meaning the wearer gives to the city he or she has decided to wear.

Scoring the Set. Jean Patou and the tennis court

In and out of the game field, Jean Patou was an innovator, shaping his definition of modernity with designs for sport and leisure.

Tennis, in its modern form, developed in the second half of nineteenth century, when Harry Gem and Augurio Perera founded the first tennis club in Lemmington Spa in 1872. Around the same time, two other people developed similar ideas: Army officer Major Walter Clopton Wingfield patented a similar game, called sphairistikè or ‘the art of playing ball’, at a garden party in his friends’ estate in Wales; Mary Ewing Outerbridge, coming home to the US from Bermuda, brought a sphairistikè set and laid out a tennis court at the Staten Island Cricket Club.

Sport ensemble by Jean Patou and Muguette Buhler, ca. 1934, Courtesy Les Arts Decoratifs, all rights reserved

The game gained a certain popularity, and as its rules evolved, many fashion designers engaged in creating dedicated ensembles. Jean Patou was one of them. Born in 1880 in Normandy, he opened his first atelier ‘Maison Perry’ in 1912 in Paris, closing it in 1914 to serve France during WW1. He reopened his boutique in 1919 and, similarly to his contemporaries Coco Chanel and Lucien Lelong, he became attracted to the new ‘active lifestyle’ fashionable in Europe and the US. Being an active person himself, the designer understood the need to study athletes and their movements to design clothes that would help them in their performances. So, in 1922 he entered the market with a line of sport and activewear, which he continued well into the 1930s.

One year before launching his activewear line, Jean Patou already ventured into sportswear, designing an innovative tennis uniform for the French athlete and Wimbledon player Suzanne Lenglen, to whom he was introduced by his brother-in-law Raymond Barbas, member of the French national team. Lenglen was a talented player; she won Wimbledon and the French Open six times each, setting a record that remained untouched for almost fifty years.

The ensemble Jean Patou designed for Lenglen allowed her to leap towards the ball and swing her racket with a full range of motion. Made of a white, pleated, knee-length skirt, a white, sleeveless cardigan and an orange headband, the outfit was considered quite a dare. The length of the skirt was seen to be socially inconvenient, as it was replacing the hat with a headband and exposing her nude arms. However, Suzanne Lenglen was not one to stick to the rules. With her emancipated flair and charismatic personality, she challenged the norms, values and restraints of ‘femininity’ within society as tenaciously as on the tennis field. A liberated and active woman, the clothes designed by Patou reflected her spirit both in and off the court.

The Emilio Pucci’s Hostess Collection at the Osaka Expo ‘70

The Marquise Emilio Pucci di Barsento, founder of the Maison headquartered in Palazzo Pucci in via de’ Pucci, in the center of Florence, was driven in his work path by the desire to liberate women, granting them freedom of movement.

Coming from a noble and influent family of Florence, he discovered his passion for the fashion design in Zermatt,Exhibition Archaeology: ‘Human Game. Winners and Losers’

To celebrate the beginning of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, we recall ‘Human Game. Winners and Losers’, an exhibition held at Stazione Leopolda in Florence in 2006.

The olympic circles are five, each one of a different colour, and they represent the world continents. together, they form the symbol of the Olympic games, not only the biggest and most comprehensive sporting event, but also the occasion in which all countries come together to celebrate unity through fair competition. The Games are a good metaphor to represent what international relationships should be: a balanced mix of patriotism and togetherness, of the specificities of each country and the universal effort put in pursuing a common objective.

Human Game. Winners and Losers, Photo by Francesco Guazzelli, Courtesy MoMu - ModeMuseum Provincie Antwerpen

Clothing is a very important part of the performative activities that go under the rather generic name of ‘sport’; at the same time, fashion has been influenced by sport in many ways, above all because of the innate power of sportswear to convey at once strength and casualness. Focusing on attire to tell something about the role of sport in art, design and life more generally was the goal of the exhibition ‘Human Game. Winners and Losers’. An initiative within the Florence 99% Contemporary, it opened in Florence on 21 June 2006, during Pitti Immagine Uomo 70. It was produced by the Fondazione Pitti Discovery and curated by Francesco Bonami, Maria Luisa Frisa and Stefano Tonchi.

Human Game. Winners and Losers, Photo by Francesco Guazzelli, Courtesy MoMu - ModeMuseum Provincie Antwerpen

The exhibition celebrated the ability of sport to built mythologies, something at which also fashion excels. the link between the two disciplines is played on the aesthetic value of sport, its ‘deep superficiality’, where everything is measured on the qualities – technical as well as apparent – of the surface. The exhibition was thematic, focused on five ‘devices’ used to disentangle the meaning of sport within culture and society: Limit; Games; Mutation; Tradition; Freedom. The display was organised as a spiral in gilt metal netting and the path was articulated in containers with different coverages: grass, asphalt, wooden boards, exercise mats.

Human Game. Winners and Losers, Photo by Francesco Guazzelli, Courtesy MoMu - ModeMuseum Provincie Antwerpen

As immersive as a real match, the exhibition wanted to be a sensorial experience, and all the elements contributed in building a very precise atmosphere – the agonistic and charged-up air of a crowded stadium; this, together with the many designs and relative ‘definitions of fashion’ showcased – from Beene to Puma + Alexander McQueen, from Patagonia to Prada, spanning from leisurewear to proper ‘competition’ attire – contributed to validate the underlying concept of the whole exhibition: how the complex encounter between fashion and sport influences behaviours on different levels, generating a lifestyle.