BlogRSS

The Vestis Talaris

Known as cassock, it is an item of Christian clerical clothing used by the clergy of Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican and Reformed churches, among others. Its name comes from the Latin term “Vestis Talaris”, which literally means "Ankle-length garment" and relates to habit traditionally worn by Jewish priests for first, and by christian

Europeana Fashion Focus: Vogue Italia editorial featuring a long dress by Missoni, 1969.

The object is an editorial page from the July/August 1969 issue of Vogue Italia; the long dress in printed lurex designed by Missoni - here presented worn by top model Twiggy and photographed by Justin de Villeneuve - is part of Missoni 1969 fall/winter collection.

THE EDITOR’S COLUMN: MASCULIN FÉMININ

Borrowing the title of the infamous 1966 movie by Jean Luc Godard, this month the Europeana Fashion blog will keep on interrogating the archives on the intricate relationship between fashion and identity, telling the stories of those objects that, for their appearance, history and use, are linked to the theme of gender.

Daniel Hechter fashion show, autumn-winter 1982-1983 women's ready-to-wear collection, Courtesy Paul Van Riel

Although greatly debatable, the binary relationship between the genders has been used to analyse both society and culture within many disciplines. Masculinity and femininity have both been defined by theorists as both a ‘social construct’ and a ‘performance’, opening up the interpretation of gender roles to various approaches and also to the individuation of other, more open and ‘queer’ definitions. From the perspectives of both design history and material culture – two areas in which fashion and clothing have been widely used as focus – the understanding of the meaning of dress and accessories in the definition of gender is central. Museums archives hold many testimonies of what men and women have used to form and perform their identity; these objects also tell stories about how people have interpreted them and, in many cases, made them symbols of their take on the so-called ‘gender quest’.

Fashion plate from "Incroyable et Merveilleuse", engraved by George Jacques Gatine, Paris, 1814, Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum CC BY SA

This month, the blog entries will unpack the complexity of the theme showcasing the myriad of possibilities in which fashion has either followed the ‘normal’ definition of gender roles – abiding by what has been commonly interpreted as precisely masculine or feminine – or the many ways in which fashion has exercised its power to subvert the social order and ‘change the rules of the game.’

We will look at what are considered the ‘stables’ of men and women’s wardrobes – the more blatant being trousers and skirts, at least from our western-biased point of view – presenting notable and sometimes unnoticed exceptions; we will deal with fashion designers and creative minds who have based their aesthetic and practices on the constant redefinition of what is masculine and what is feminine, in the design and production of their pieces as well as in their representation in ads and campaign; we will look at performativity, and more precisely, at performance, as a way to visually define a ‘stage identity’ which sometimes ends up merging with the ‘real’ self (if such thing exists anyway).

Follow us in our journey to find out if, how and in which ways objects have helped men and women in their definition and representation, ultimately acquiring a gender for themselves.

Europeana Fashion Tumblr Curation by Beeld en Geluid!

The Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision is presenting through this month a selection from its multimedia archive on Europeana Fashion Tumblr.

The Uniform, Irony and Eroticism

Uniforms stand at the meeting point between fashion and power. With their ability to define roles, in particular contexts their importance reaches a different level - above all when irony and eroticism get involved, contributing to their timeless appeal.

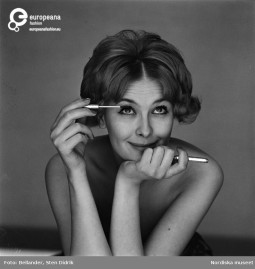

Written on Her Face: the Power of Make-Up

Uniforms can come under any form and aspect, and serve as devices to create the image of ourselves we want to put forward. This is particularly true for everyday, personal uniforms – what we decide to wear in order to ‘be’ the person we want to be. Amongst the many kinds of uniform that we might think of, surely make up holds a special place, since it sits between the idea of something ‘disposable’, which can be put on and off, and that of something so necessary to become natural – and simply unavoidable.

Trends in make up – as the parameters of beauty – have shifted throughout time and space but, in the Western world, it is especially during the twentieth and nineteenth century that their popularity has grown. At the beginning of 1900, a pale complexion was a must amongst rich and educated people, because this differentiated who didn’t have to stay out in the sun to earn a living from the people who had to work. Compacts containing power were then one of the only objects associated with make up that was appropriate for women to carry around; some of them were very elaborate, as pieces of jewellery, and enriched with initials or incisions.

During the 1910s, make up was not popular, since it was associated with prostitutes; it’s probably with the rise of popular icons, whose image served as model to shape tastes and form styles, that make up really took off both on the market and in visual culture. So, together with their outfits, the make up of the likes of Greta Garbo, Ava Gardner, Audrey Hepburn, became a fixed feature of their age, necessarily weighed on the development of new items and the diffusion of different products. Mascara, for example, was firstly invented by Eugene Rimmel in 1913, while lip gloss was introduced by Max Factor in the late 1920s, but the popularity of these products came with the use by actresses on the big screen, and also by rather strong marketing campaign based on the benefits women would get by using make up regularly.

Interestingly, the history of cosmetics is linked to two incredibly savvy businesswomen. Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden, always depicted as opponents in the market, share the merit to have established the use of cosmetics as not only proper, but also necessary to the appearance of a woman. Helena Rubinstein marketed the mascara and made it very popular, while Elizabeth Arden used her advertising to talk to women to convince them that being beautiful – at every age or class – was synonymous with being appropriate, and thus, at least in Arden’s view, powerful.

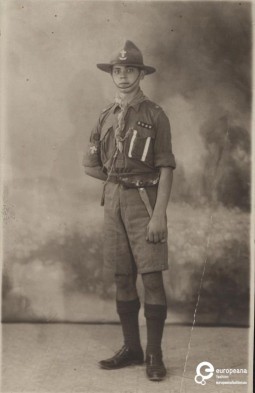

Scouting for a Restyle: Designing Uniforms

In 1980, the uniform of the Boys Scouts of America had a restyle. Its previous militaristic look, which hadn’t received a complete overhaul in over sixty years, had been reinterpreted by no other than the infamous fashion designer Oscar de la Renta.

Small but full of pride: pins and badges as uniforms

In the rush of everyday life, most people may refer the act of dressing ‘unconscious’, considering it a routine activity that does not require a high level of attention. Surprisingly enough, the details – and thus the smallest objects – are the one requiring the biggest effort, since they have the power to become ‘wearable statements’ – which makes them real uniforms.

This is true for those objects that were created especially to signal some kind of belief, political affiliation, or support to a cause. Badges, pins and insignia have the power to subvert the meaning of a dress, becoming themselves a uniform on their own right; they can convey messages and meanings that a whole attire would represent. Badges rely on the striking visual power of their design to separate who wears them to ’the others’. Within the military – one of the environments in which these kind of objects are more valued – pins and badges are often given as prizes, recognitions of honour and pride. The symbolic value of the badge is enhanced by ceremonies organised precisely around the act of ‘decorating’ a person with a quasi-sacred object. Badges can also offer comfort to those wearing it, because they define, to themselves as well as to the others, what they stand for, and thus serves as sign of belief and ultimately, of identity.

Maybe these senses of ‘pride’ and of ‘comfort’, of which badges are usually infused, are what led to the use that the LGBT community has been doing with objects of this sort – be it badges, pins, or other ’symbols-to-wear’. The gay community has depicted its icons – the ones that formed its vocabulary and then its visual identity – on badges and pins that are worn not only by members of the community itself, but also by supporters and, more broadly, by people sharing the values of emancipation, equality and liberty. The most famous symbol is surely the rainbow flag, created in 1978 by the American artist Gilbert Baker as a symbol of diversity, respect and tolerance. This symbol has been translated into pins and other objects, building a common language for an incredibly diverse group of people, coming from different geographies and social classes.

The badges shown in this post were produced and used during the Stockholm Pride in 2008, year in which Stockholm also hosted the Europride Festival, presenting itself as the international capital of freedom and social progress. Nordiska Museet holds a complete documentation of Europride/Stockholm Pride 2008, with interviews, photographs and objects, including articles about the different social services that participated in the Pride celebrations: an amazing project of ‘archiving the present’.

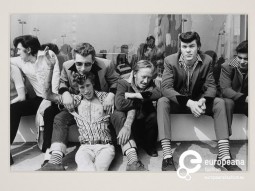

Teddy boy – wearing a uniform to be different

Teddy Boys -dressed with long, narrow lapelled, waisted jackets, narrow drainpipe trousers, ordinary toe-capped shoes and a fancy waistcoats - were one of the first youth groups to differentiate themselves as teenagers, weighing in the emergence of a youth market.

Europeana Fashion Focus: Ensemble by Yohji Yamamoto, A/W 2000/2001

The outfit is composed by a hooded jacket and a long skirt. Both pieces are in cashmere wool, and present different patterns, recalling traditional Indian designs; the finishings are in coyote fur. It was part of autumn/winter 2000/2001 collection by japanese fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto.