Archive for March, 2017

Runway Archive: Vivienne Westwood, Pitti Uomo 38, 1990

The image shows an outfit designed by Vivienne Westwood for her s/s 1991 collection shown at Pitti Uomo 38. The model wears a white shirt in a loosely weaved fabric under a denim oversized jacket, whose proportions and lines remind of a sixteenth century doublet. In particular, its punched texture recalls the one worn by the Tailor in the infamous painting by Giovan Battista Moroni.

The British fashion designer Vivienne Westwood is known for her use of the past to find inspiration for her collections. Her own version of nineteenth century Victorian figures or Parisian cocottes are considered a milestone of fashion history. Although her vision is romantic, however, the designer’s practice is very much merged in the present. her revoluntary activities and ideas allow her to use fashion as a way to raise awareness on topical issues of contemporary times.

Bruno Pieters: Time Conscious

The influence of time over fashion also concerns its production; even if from a mere economical point of view, time has a big impact on the production costs and the final price of a garment.

In this sense, time is such a topical theme today that brand’s focus over faster or slower production techniques can determine the very identity of a brand. Being conscious of time and its value is an important quality for designers, not only for the definition of their aesthetics but also for shaping their approach towards the production and commercialisation of their clothes.

'Delyth', dress designedby Bruno Pieters, 2004. Courtesy MoMu - Modemuseum Provincie Antwerpen, all rights reserved.

From June to July 2016, Antwerp hosted the exhibition ‘Beyond the Clothes’, curated by Bruno Pieters. The exhibition displayed the ways the Belgian fashion designer approached these issues with his own project and website, Honest By. Bruno Pieters. This project, launched in 2012, aimed at stimulating costumers’ consciousness over themes such as sustainability and transparency.

'Tatja', dress designedby Bruno Pieters, 2005-06. Courtesy MoMu - Modemuseum Provincie Antwerpen, all rights reserved.

Bruno Pieters, who graduated from the Royal Academie in Antwerp in 1999 and gained experience at Christin Lacroix, Maison Martin Margiela and Josephus Timister, first started with his website, which he created after a two years long hiatus. In it, for each piece on sale, he described in details the manufacturing process and the information of the materials and accessories.

These details serve not only to retrace the story of the garment back from its conception but also to keep trace of operation and works that, beyond the clothes, usually remain invisible or untold. What lies beyond clothes, in fact, is the craftmanship of a group of authors and interpreters that convey their knowledge and experience to the realization of the product. Therefore time acquires a great importance as it is the direct expression of their contribution abd one of the key terms to value it. At a time when fashion and its industry speed up their pace to the extreme, the consciousness of the time needed and its costs are essential to understand, and maybe defend, the right to take it.

Temporal Meditations: Hussein Chalayan at Pitti Immagine 64

For the 64th edition of Pitti Immagine Uomo, Hussein Chalayan showed his first men’s collection, developed in collaboration with Pitti Immagine. The designer decided to mark his debut in menswear presenting Temporal Meditation, the first movie he wrote and directed.

The movie premiered on 19th June 2003 at Teatro della Pergola in Florence. It was shot in Athens, and saw as protagonists the photographer Mark Segal and Sophie Hill, a Greek actress. Even though it was the first time that Chalayan presented himself as film director, he was not new to experimentations that could combine fashion and art. He was well known for blending art and fashion in his own practice, working both within the fashion system and in art galleries.

The movie is 20-minute long; the action takes place in an airport, a liminal non-place where the boundaries between different countries seems to be negates, and time suspended. the narrative is constructed by many themes: identity, memory, time. Chalayan used genetic anthropology to draw the ethnic paths that crossed Cyprus, his homeland, within space and time. This interest in human geography and migration is very dear to the designer, who constantly refers back to the idea of ‘homeland’ as constant reference characterising his fashion and artistic production.

The press release of the event states: “Historical discourse has exemplified a view of time as sequential and progressive which has been embalmed through the use of the printed word. Garments can be viewed as an archaeological talisman which morphs slivers of past and present, ultimately and perhaps paradoxically becoming a frozen fragment of its own archaeological quest”.

The movie proposes to consider clothes as symbols holding together different chronological dimensions; In their being material memories of an undefined past that still bear sign of the present, they become traces that have to be rediscovered through quasi-archaeological techniques in order to reveal their meaning. This way, clothes have the power to negate the linearity of the time of history proposing instead a chronology dictated by feelings, memories and emotions.

Runway Archive: Lapidus, Autumn-Winter 1996, Couture

The picture shows a model wearing a full, long, taffeta skirt and a long-sleeved white top with deep square neckline. A globe is printed on the front right of the skirt. The model, also wearing a pair of long and colourful earrings, is posing for the photographers, with her hands in the small pockets of the skirt. The look belongs to the A/W 1996 Couture collection of Lapidus.

Edmond “Ted” Lapidus was a French fashion designer. After an apprenticeship with Dior, Lapidus founded his fashion house in 1951, gaining popularity during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1989 Ted Lapidus’s son Oliver Lapidus took over the label. In 2000 Lapidus stopped the couture line, and since then the label produces fashion accessories like watches and fragrances.

Exhibition Archaeology: Spectres. When Fashion Turns Back

Fashion spans many temporalities. While being projected to the future, it constantly looks back to the past to which it strongly relates. As explained by Walter Benjamin with the image of the ‘tiger’s leap’, fashion interacts with history in many and different ways. Back in 2004, curator and exhibition maker Judith Clark explored this haunting relationship in the exhibition ‘Spectres. When Fashion Turns Back’.

The exhibition 'Malign Museus. When Fashion Turns Back' at MoMu - Fashion Museum of the Province of Antwerp, photo by Tim Stoops, 2004. Courtesy MoMu - Modemuseum Provincie Antwerpen, all rights reserved.

The exhibition was first installed at MoMu, in Antwerp, from September 2004 to January 2005 with the title ‘Malign Muses. When Fashion Turns Back’ and later at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, from February to May 2005. As explained in the catalogue of the exhibition, it took shape after a two years long conversation between Clark and the fashion theorist Caroline Evans, author of the seminal text ‘Fashion at the Edge’, whose suggestion and ideas served as an inspiration for the real-life devices that characterised the set of the exhibition.

The display recalled the dark atmosphere of the Victorian circuses and freak shows; it used devices such as toys, carousels and lantern slides tricks to evocate the ghastly bound between fashion and history and to articulate the complicate and introspective sections of the exhibition, in which the creations of contemporary designers where shown alongside historical pieces in suggestive juxtapositions.

The exhibition 'Malign Museus. When Fashion Turns Back' at MoMu - Fashion Museum of the Province of Antwerp, photo by Tim Stoops, 2004. Courtesy MoMu - Modemuseum Provincie Antwerpen, all rights reserved.

The sections of the exhibition were: ‘Reappearances: Getting Things Back’, ‘Nostalgia’, ‘Locking In and Out’, ‘Phantasmagoria: The Amazing Lost and Found’, ‘Remixing It: The Past in Pieces’, ‘A New Distress’ and, in Antwerp, ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’. They explored the modalities through which fashion turns to the past through the results of these various operations. If history serves as a source of inspiration, it also represents a bound to be broken or ignored to move forward, an instrument at the designers’ disposal for the invention of new stories with clothes.

The exhibition 'Malign Museus. When Fashion Turns Back' at MoMu - Fashion Museum of the Province of Antwerp, photo by Tim Stoops, 2004. Courtesy MoMu - Modemuseum Provincie Antwerpen, all rights reserved.

Contemporary designers, such as Junya Watanabe, Dries van Noten, Viktor and Rolf, Simon Thorogood, Hussein Chalayan, Shelley Fox and Rei Kawakbo, featured in the exhibition; their creations were put in dialogue with those of earlier couturiers, such as Schiaparelli, Madame Grés, Jean Dessès and Dior, and previous century costumes, to highlight the references and similarities: all the elements contributing to a discourse that draws back and puts forward the figures inhabiting past and present, to tell new, compelling stories.

“Gianfranco Ferré. Moda, un racconto nei disegni”: Exhibiting the Process and Poetic of Fashion Design

From the 21st April, Centro Culturale Santa Maria della Pietà in Cremona, Italy, will host ‘Gianfranco Ferré. Moda, un racconto nei disegni’, an exhibition dedicated to the sketches and drawings by Italian fashion designer Gianfranco Ferré.

Silk taffeta and silk velvet cape with topstitching. Silk velvet dress. Alta Moda, Fall/Winter 1988. Pencil, fine black felt-tip pen, colored felt-tip pen on construction paper. Courtesy Fondazione Gianfranco Ferré, all rights reserved.

An architect by formation, Gianfranco Ferré has been one of the greatest name of Italian fashion. With his sapient use of sartorial construction, materials and decoration, he introduced a new sensibility in fashion, frequently represented by his iconic creations.

Silk grisaille trench coat. Prêt-à-Porter, Spring/Summer 1988. Pencil, fine black felt-tip pen, colored felt-tip pen on construction paper. Courtesy Fondazione Gianfranco Ferré, all rights reserved.

The exhibition ‘Gianfranco Ferré. Moda, un racconto nei disegni’ is curated by Rita Airaghi, Director of the Fondazione Gianfranco Ferré, and was developed with the collaboration of the Municipality of Cremona. While including some of the garments he designed, it will focus on his hand-signed sketches and drawings, one of the most fascinating artefacts of the designer’s creative process. Quoting Gianfranco Ferré himself: “For me drawing means jotting down on paper a spontaneous idea which I can then analyse, check, verify and finetune, reducing the basics to precise concise lines set on diagonals and parallels within geometric shapes and figures… as both a fashion designer and an architect I see fashion as a form of design…”; either elaborate and detailed or more essential and instinctual, the selection of over one hundred sketches on show in Cremona tells the history of the vision, passions and ideals of the poetic fashion creator, as well as unveiling to the public a part of his unique creative process.

Printed silk and lurex caftan with embroideries and sequin appliqués. Prêt-à-porter, Spring/Summer 1990. Pencil, fine black felt-tip pen, pastel crayon, gold powder on construction paper. Courtesy Fondazione Gianfranco Ferré, all rights reserved.

While fixing on paper the necessary information to turn the fashion designer’s ideas into material creations, these drawings are also greatly evocative artworks; they show the idea of beauty, harmony and style that the designer developed and improved during his prolific career both at his own brand and as the creative director of the Maison Christian Dior, where he worked from 1989 to 1997. More than instruments, these drawings are a statement of Gianfranco Ferré dedication to fashion design, an important working method and an indispensable key to comprehend the work of Gianfranco Ferré both in its materiality and his aesthetics.

The exhibition will be open until the 18th June.

Europeana Fashion Focus: Scooter designed by Emilio Pucci, 1947

The photo portrays a model of scooter designed by Marquis Emilio Pucci at the end of the 1940s.

This scooter, made of smooth lines and an overall essential design, testifies the versatility of Emilio Pucci, both in interests and aesthetic; in fact, it is an object not directly linked to clothing, but concurring to the definition of fashion as part of lifestyle; moreover, it does not bear any sign of the graphic style that characterised the later fashion production of the designer.

The scooter was designed, together with another similar exemplar, in 1947. In the same year, the Marquis had set up a sport, casual and leisure clothing company. His passion for sport translated into the development of collections focused on leisure activities, such as sky and, indeed ‘scooter racing’, directed to an active woman, projected to the future. This interests led, in 1957, to the design of the ‘Vespa’ dress, and to a collaboration with Piaggio, the Italian manufacturer of the iconic scooter, at the end of the 1970s.

The object is part of Emilio Pucci Archive. Discover more on the Europeana fashion portal.

Runway Archive: Salon Johanna Marbach, ca. 1916.

Fashion show in Salon Johanna Marbach, photo by 'Atlantic', Berlin, ca. 1916. Courtesy Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC BY NC SA.

The picture shows a model posing in an nineteenth century interior, with three women, probably clients, looking carefully at the model while sitting on chairs. The model, standing straight, is wearing a knee-long redingote with fur collar, cuffs and lower hem. Underneath the coat, is an an ankle-lenght skirt, worn over black tights and low-heeled shoes. On the head, the model is sporting a flat hat with wide straight brims.

Differently from nowadays nearly public shows, whose grandeur is usually streamed on the Internet, in their early stages fashion shows were private events that involved few guests. In-house models were dressed in the maison’s creations and sent on a proper stage, with potential clients as audience. The clients would chose their favourite looks, to later discuss the eventual details for the finalization of their new silhouettes. In this original photography by ‘Atlantic’, the clients are assisting at the fashion show of designer Johanna Marbach in Berlin. Marbach was a designer active in the first two decades of the twentieth century, who also designed the costumes for films of Carl Froelich and William Dieterle.

Faire sa Toilette – Time for Dressing Up

The term ‘toilet’ holds in itself many temporalities, from the fast and rapid, to the long and elaborate. It indicates the process of dressing or grooming oneself, a morning ritual that is, and has been, both a private and public.

In origin, the word indicated, namely, a ‘little cloth’ that was placed over someone shoulders during the process of hairdressing to protect the dress from the eventual moistures and powders used for combing. During the seventeenth century its meaning changed to include, for metonymy, the process of grooming and dressing at the dressing table.

'Modethorheit: Les Dames vivent en Paris', caricature, Johann Martin Will, 1775-76. Courtesy Dietmar Katz, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC BY NC SA.

Only in the 18th century however an audience started to be involved in the ‘toilet’, which before was a rather intimate daily practice to be done ‘behind closed doors’. In fact, while its early stages, including grooming and sponge-bathing, were spent privately with a maid, the later stages, that involved hairdressing, picking clothes and writing letters, close friends and guest were invited to assist.

'Le bon genre, No. 39: Les Titus et les Cache-folies', caricature, Pierre de la Mésangère, 1812. Courtesy Anna Russ, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC BY NC SA.

These ‘toilet-calls’, as they were named, exposed the intricacies and magnificence of this ritual that was as fascinating as its participants were wealthy. It captured the imagination of writers and painters, who documented these ceremonies and described them in their extravagant details, as did the poet Alexander Pope in ‘The Rape of the Lock’. The toilet, however, was not an exclusive practice for women. Men, and in particular dandies and their precursors, the ‘macaroni’, spent many hours at the toilet for their dressing up; George Brummel, for instance, used to invite the Prince Regent, the future King George IV, at his morning ritual.

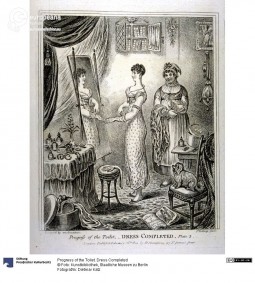

'Progress of the Toilet. Dress Completed', caricature, 1830. Courtesy Dietmar Katz, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC BY NC SA.

In the representation of the toilet, the objects, the gestures and time served as props to construct the grandiosity of these moments spent at dressing up, and of the women and men taking part in it. Time indeed, was what toilets were about. What the lengthy toilet really represented was, in fact, instead of one’s vanity, one’s possibility and the will to take time, and spend it, in the ‘fundamentally ephemeral’ act of dressing and grooming oneself.

Watches: Time as Material Luxury

To understand time was one of the first necessity experienced by human beings. This led to the invention of devices that could help keeping track of time passing: watches. Both as ‘public’ objects and personal belongings, watches soon became artefacts that gathered scientific expertise and high-manufacture skill.

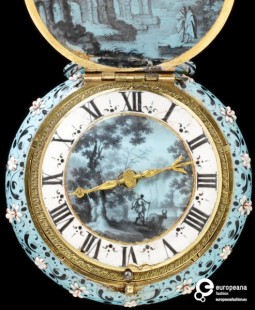

Watch with a case and dial of painted enamel and gilt brass, England, ca.1640, Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum CC BY

The pocket watch developed in sixteenth century as mostly ‘masculine’ object, and consisted in a timepiece made wearable thanks to a chain. The round shape – the most common – is the reason why they were also called Nuremberg eggs, and worn around the neck. It is said that it was Charles II of England who introduced the trend of wearing the watch in the pocket of waistcoats: this led to changes in size and, above all, styles.

Chain watch with hook and compass, 1850-1900, Courtesy ModeMuseum Provincie Antwerpen, All Rights Reserved

The pocket watch, or fob watch, a stable of the gentlemen’s attire, was substituted by the wristwatch, which developed after the so-called trench watch, a transitional object used by the military in World War I. Interestingly, watches to be worn on the wrist before the 20th century were mostly used by women. The oldest surviving was in fact made in 1806 and belonged o Joséphine de Beauharnais. Other sources account for a watch made for Countess Koscowicz of Hungary by the Swiss watch manufacturer Patek Philippe in 1868 as the first artefact of this kind.

Even though their invention came ‘out of necessity’, today we tend to link watches – above all, the most decorated, precious and iconic in design – to an idea of luxury; this maybe because, in our speeded up reality, time itself might be a luxury.