Archive for December, 2016

‘Duchess of Savoy’ Fancy Dress

For the last blogpost of the year, we decided to treat ourselves with the interesting story of an amazing ballgown picked from the Europeana Fashion archive.

the fancy dress costume consists of an embroidered silver satin dress and lace ruff, and was made in England in 1897. The costume is embellished with pearls and silver strips; it has a low round neckline, large slashed and puffed sleeves with tight lower sleeve covered in pearls, jewelled girdle. The dress was given by Lady Victoria Wemyss, Duchess of Portland, to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The Duchess of Portland dressed as the Duchess of Savoy, 1897, at the Duchess of Devonshire’s Diamond Jubilee Ball, © National Portrait Gallery, London, All Rights Reserved

Lady Victoria Wemyss was an intimate of the royal circle: her father, the sixth Duke of Portland, was Master of the Horse to Queen Victoria and her mother, the Duchess, later Mistress of the Robes to Queen Alexandra. Lady Victoria, probably the last surviving godchild of Queen Victoria, was for 57 years an Extra Woman of the Bedchamber to her cousin Queen Elizabeth.

Lady Victoria Wemyss was the subject of a photograph that is probably the earliest surviving commercial work by the photographer Alice Hughes. In the photograph, now part of the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, she is wearing the dress she donated to the Victoria and Albert museum. The dress – which ‘transformed’ Lady Victoria in the Duchess of Savoy – was worn in occasion of what has been called the ‘social event of the year’ 1897, the Duchess of Devonshire’s Diamond Jubilee Costume Ball.

Venus in Feathers: Boas of Paradise

There are materials that alone can give an aura of preciousness to the garments or accessories they are part of. This is true for beads and jewels, but also for fur and, above all, feathers, whose very nature is able to turn the ordinary into something astonishing.

Lady with feather boa, drawing by Herbert Mocho, 1935 ca., Courtesy Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin CC BY NC SA

There are two main types of feathers: contour and down. Contour feathers cover the wings and tail, while the down feathers, shorter, softer and fluffier, are to be found at the base of the contour feathers. The use of these precious materials in personal adornment really does cross times and cultures.The craze for feathers let to great damage to the animal world: the bittern, for example, was extinct due to the immense demand during the nineteenth-century, a destiny shared with the huia of New Zealand, which happened right at the beginning of twentieth century. Now national and international legislations are very strict, to protect species that are greatly reduced; also, advancements in technology made it possible to produce fake feathers and fur that look and feel real.

When talking about feathers and fashion, it is not much a matter of need, but definitely a matter of appearance and spectacularity. The more exotic and flamboyant the feathers orating dresses and accessories, the better, above all in attires for parties and events. And, if many accessories, as hats and bags, have been decorated with feathers, one fashion object can be said to be the real celebration of the material and of all its potential: The feather boa.

It is claimed that this ‘long muffler made of feathers’ was invented by Henri Bendel at the end of nineteenth century, when it was used above all by the ladies of high society for special occasions; even though there are accounts of similar items since the mid-1800, its popularity grew substantially during the 1920s, and then again in the 1970s, the late 1990s till the early 21st century. Interestingly, the fame of the boa is linked to the stage; boas have been used by dancers and entertainers in general to perform their acts: for instance, dancer Isadora Duncan and actress Mae West used it.

the appropriation of this object from some sectors of popular culture considerably changed its meaning and, therefore, the kind of ‘elegance’ it bears. Some of the most mesmerising and ‘campy’ personalities, such as David Bowie, Cher and Elton John used to wear boas as ‘props’ in their performances. It was – and still is – also a staple of cabaret and drag shows, which appropriate of the objects defining the look of the ’ladies’ turning them into caricatures.

The Brides of Greece and Cyprus at the Leventis Municipal Museum

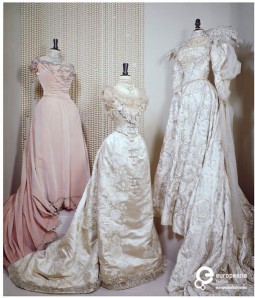

A new exhibition brings together over two centuries of bridal costumes from the collections of the Leventis Municipal Museum of Nicosia and of the Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation of Nafplion.

With some exceptions, differences and peculiarities, marriage is an institution present in all cultures. Many are the elements that define every marriage tradition, making them vary from country to country, region to region, even town to town or family to family. Among these elements, the bridal gown stands out as the first and maybe as the most apparent. In a new exhibition, the Leventis Municipal Museum of Nicosia gathers the costumes of two countries history has both united and divided: Greece and Cyprus.

Nicosia, 1967. Bride: Fotini Michaelidou of the Leventis family. Fashion House: Lanvin, Paris. Collection: Foundation «Polycarpos Yiorkadjis».

‘Brides at the Leventis Museum: tradition and fashion in Greece and Cyprus’ features pieces from the collections of the Cypriot museum and the Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation. The bridal gowns on show range from the late nineteenth century to 1974, covering over one hundred years of historical and social events, culminating with the year 1974, chosen by the curator of the exhibition as the year in which ‘the centuries-long order of things of the indigenous population was ruptured, dramatically and irrevocably changing the socio-economic structures’.

Distinguishing between wedding gowns from the city and the village and between those of wealthy and less privileged brides, the exhibition focuses on the similarities and differences between the dresses of the Greek area and those from Cyprus, comparing their length, width and materials showing how they have been influenced not only by national and regional history and traditions, but also by movies and royal weddings.

The exhibition explores the changes of the wedding gowns in relation to the events that characterised the two countries during the period, including two World Wars and the independence of Cyprus. The dresses show the changing approach to the very practice of marriage, such as the abandon of the use of traditional garments and the harmonisation with international fashion, or the introduction of the ‘white wedding dress’ after the one worn by Queen Victoria of England for her wedding with Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1840.

The exhibition will be on show until April 23rd 2017. Visit the Leventis Municipal Museum of Nicosia website to learn more.

Valentino Garavani

Standing out for his elegant and charming creations, Valentino Garavani, known to all simply as Valentino, has established himself as one of the top designers of Italian couture.

Born in Voghera, Italy, in May 1932, Valentino debuted early in fashion; in fact, he started very young as apprentice for local designers, including his aunt Rosa. His formal training took place later in Paris, where after graduating at the École des Beaux-Arts and the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, he had his professional start in haute couture working for Jean Dessès and Guy Laroche. In 1959 Valentino came back to Rome and opened his fashion house one year later in partnership with Giancarlo Giammetti. The couple in business and in life modeled their business on the grand houses Valentino had seen in Paris and developed it into an internationally recognized brand.

Red dress designed by Valentino. 1971. Courtesy of MUDE - Museu do Design e da Moda, Colecção Francisco Capelo. All rights reserved

Valentino based his work on the desire to accentuate a woman’s sensuality with his clothes; his debut in the same year of the launch of Federico Fellini’s “La Dolce Vita” probably accelerated his success as women everywhere wished to emulate the film’s style and its star Anita Ekberg. Since his early shows Valentino drew praise for his full-length romantic skirts and his style was immediately recognizable for dresses made in a particular shade of red, now known as “Valentino red”, which still characterizes the label. In 1967 he was awarded with the prestigious Neiman Marcus Award for his ”no-colour” collection, in which he featured a palette of beige, white, and ivory hues.

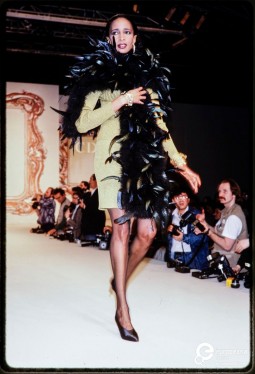

Model on catwalk for Valentino's final show at the Musée Rodin in Paris. Spring Summer 2008, Couture collection. Courtesy of Catwalkpictures. All rights reserved

Since the very beginning Valentino’s unique and feminine designs have enchanted the women known for their allure and personal style. One of his first most prominent client was Jacqueline Kennedy, who in 1964 ordered six dresses in black and white to wear during the year following the assassination of her husband, President John F. Kennedy; in 1968 Valentino also designed the dress that she wore for the wedding with Aristotle Onassis. But she is not the only iconic personality the Valentino’s signature was linked to; the Maison has been chosen several times by Hollywood actresses and remains a staple in the wardrobe of socialites and other personalities.

As a leading fashion designer who contributed to build the fashion system that we know today, Valentino worked with the most legendary models including Naomi Campbell, Claudia Schiffer and Eva Herzigova, who took part to his final show at the Musée Rodin in Paris in 2008, cherishing the maestro before his retirement.

Documenting TheArts+: Interview with IUAV and POLITECNICO DI MILANO students

Today we present the second round of interviews to the students who took part to the workshop THEARTS+. Here are the answers Giulia Profeta from Politecnico di Milano and Eugenia Ioppolo from IUAV University of Venice gave us.

Europeana Fashion: First and foremost, can you tell us something about yourself? How and why did you become involved with fashion?

Giulia: Right after high school, I was very confused: I was thinking about engineering, economic, medicine, all scientific fields which were close to my training, but that did not really interest me or made me curious. Then, in between the proposals for study at Politecnico di Milano, I found the design courses, particularly for fashion and, although I was a bit scared, I decided to give it a try, and I don’t regret it. I got my BA in fashion design with specialization in knitwear and now, always at the Politecnico di Milano, I am attending a Master in Design for the fashion industry. The course has quite a wide span, from projects for sportswear brands such as Decathlon and SLAM, which are aimed at exploring new technologies, to communication skills and marketing.

Eugenia: I do not know exactly how I came to study fashion: it has always been a field that has intrigued me. I enrolled in the degree ‘Fashion and costume science” at the Sapienza. There I fell in love for the very relationship between art and fashion, and how this relationship has developed through history and according to different personalities. Two years ago I joined the graduate program in “Visual arts and fashion” at IUAV of Venice. There I learned to juggle theoretical courses – which cover both the fashion that art – and practical workshops – sewing, design, knitwear. At the beginning of the second year I left Venice for an exchange at Stockholm University, where I followed some courses focused specifically on research. I’m currently writing my thesis.

EF: Tell us your experience: how was the workshop? What are the main features of the project developed by your group?

G: We had three days of intensive work with specialists who shared with us their professional skills. The app developed by my group is called VISUALIZE and can be defined as a library that offers daily digital images from different categories of interest: the user can choose whether to deepen the proposed theme, leafing through the tunnel and save his or her favorite pictures, or change theme. Surely there are things that can be improved, but in its simplicity I personally find it very useful; in fact, thanks to the possibility to create folders, the user can save and move on to review the contents: this is very important for a designer or a creative, because it is easy to select images to realize mood boards, concept, or perhaps find inspiration for the prints.

E: The workshop was quite challenging and interesting. The first day we were introduced to the Europeana project. We started developing some individual projects, related to the Europeana Fashion contents. Then six projects were selected, we got divided into groups and each group had to develop one project and create a business plan. Finally, we presented our projects in front of the board that was responsible of selecting the ‘winning’ idea. The project chosen was ‘Fantasia’, the one I have been working on with two other girls: Tetiana Baran and Victoria Dubinina. The work to which I took part was born as ‘Dressformer’, which was a free software that would allow to create new styles of clothes. But this project has since proved very weak and so we have continued to develop it and change it until we got to ‘Fantasia’. Dedicated especially to illustrators and fashion designers and interior designers, the program was aimed at creating new patterns. Clients, with a search of images made available through Europeana, could decide which ones to use and could modify them – using a special design, a color, combining multiple images – to create unique patterns. All of this, while remaining connected, thus directly creating an online portfolio, and especially having the program always at disposal.

EF: We are curious about your general impressions on the experience: did you like? Did you find this useful? You can use it in your path of personal study?

G: My impression is definitely positive: it was set in a very professional manner, and although we had not experience as app designers, organizers and experts have been helpful in explaining very simply how this sector works. I found particularly useful and interesting the explanation about how to make a business plan, and the final confrontation with the board; I believe that a good designer should always keep in mind the market and the limits of his or her projects.

E: In general I found the experience quite positive, even though a bit tiring: times to think of new and interesting ideas and turn them into projects were very tight. The part that I found most interesting, however difficult because I have no basis in economics, has been that relating to marketing. Thinking and creating a business plan of the project and above all making a good presentation allowed me to get involved and especially to acquire the knowledge that I missed. In particular, having to work in a group with other people who I did not know, with different paths of study and ways of thinking has enriched me so much.

EF: As a fashion student, how do you think you might find useful products such as those developed by the various working groups?

G: I think that Fantasia, the winning project, could be a great starting point to experience digital content. It is very simple and I think it can be both useful for creatives and designers, and fun for the general public, since it can turn the experience into a game for users who are not working in the fashion industry.

EF: Do you use digital platforms in your creative practice? If so, what and how you use them?

G: I mainly use Pinterest for my research, and to create moodboards. I visit quite often online shopping sites of the brands that I believe may be the main competitors for the type of project I am working on, to ‘spy’ what the market offers and to differentiate myself. Since I believe that in the fashion communication is very important, I often visit a site called ISUU, which collects magazines and publications.

E: In my career as a fashion student, I used a lot databases like Pinterest and Tumblr for the visual research, especially for labs and to develop my collections. I also find very interesting the work done by Academia.edu, a website for researchers, dedicated to the sharing of scientific publications and essays.

The bias cut – a hint of elegance

A bias cut garment is essentially a dress whose fabric is cut diagonally. The result of this operation gives these garments a very peculiar look: they tend to cling to a woman’s curves with a delicate, graceful – and sensual – flow.

The bias-cut technique, still in use in contemporary pattern making, initially appeared in the work of the Parisian couturière Madeleine Vionnet in 1927, who used it to introduce a new silhouette that later came to characterise the 1930s. Inspired by Classical Greek fashion, Vionnet’s aim was to create feminine and romantic gowns to emphasize the contours of a woman’s body, in contrast with the popular designs of that time, which tended to hide them. The introduction of the bias cut signified a move away from the tubular fringed and beaded chemise dresses of the 1920s.

Bias-cut evening dress by Madeleine Vionnet. 1936. Courtesy of Les Arts Décoratifs, Paris. All rights reserved

The period between the two great wars was characterized by austerity and restraint and the trend went for unadorned garments created by the manipulation of geometric forms such as square and quadrants. The technique developed by Madeleine Vionnet consisted of cutting the fabric at a 45 degree angle, instead of on the grain. This allowed the fabric to drape easily over the woman’s body with a more elegant result. Her invention arrived after various experimentations with cutting techniques, started in 1910. Vionnet was influenced in her approach by the Callot Soeurs, where she did her apprenticeship, and later by Jacques Doucet, where she learned how to incorporate classical techniques of garment construction involving minimal cutting.

Bias-cut slip dress by John Galliano. Autumn-Winter 1997, Womenswear collection. Courtesy of Catwalkpictures. All rights reserved

Due to the nature of the cut, the new technique required several more yards of fabric, which made bias-cut of difficult reach of women during the Great Depression. However, Its sensuous glamour was firstly appreciated and adopted by Hollywood screen sirens as Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo and society elite like the Duchess of Windsor. In 1933 Gilbert Adrian, head of costume at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, designed a satin bias-cut gown for Jean Harlow for 1933 film “Dinner at Eight”. It had a big success and popularized Vionnet’s new design for an American audience.

The invention of the bias cut is completely attributed to Madeleine Vionnet, also known as the “Queen of the bias cut”, and it is considered her greatest contribution to fashion. In 1990s John Galliano revamped the technique and and introduced the lingerie-inspired slip dress, popularized by Kate Moss and surprisingly worn by Lady Diana at the Met Ball in 1996, bringing a technical innovation invented years before into the realm of popular culture.

Documenting TheArts+: Interview with POLIMODA students

From the 19th to the 23rd of October, within the context of the Frankfurt Book Fair, Europeana hosted a series of workshops in the context of the Arts Plus (http://theartsplus.com/). Europeana Fashion selected participants amongst three leading fashion school belonging to its network: Polimoda, IUAV University of Venice and Politecnico di Milano. The students took part in different workshops, led by the Spanish commons organisation Platoniq and by the international consultancy company Media Deals, playing with the data hold in the Europeana collections and thinking creatively on how to use them for their projects. The various activities involved developing business models and learning how to best present and promote the projects, as well as finalise them and pitch them to investors.

We have asked some of the participants to share their thoughts on the experience. Here is what Rachele and Elizaveta, two participants from Polimoda, told us.

Europeana Fashion: First and foremost, can you tell us something about yourself? How and why did you become involved with fashion?

Rachele: After attending high school in my hometown, Cecina, I decided I to enroll at POLIMODA because I needed a change: I was looking for something that could take me away from normality. Then I started the Fashion Design course, which is mainly focused on techniques and practical knowledge: models, graphics and a smattering of business. I enjoyed the course above all because it allowed me the freedom to choose how to shape and develop my own project.

Elizaveta: I am currently studying at the Fashion Design course at Polimoda, an institution that I am very happy to have chosen: the environment is conducive to any kind of creative development and the teachers are always available. The courses are mostly practical, and give you the right preparation to develop a project in its entirety. There has never been a concrete reason why I chose to study fashion: maybe just the fact that I have always seen fashion as an environment where creativity has not limits. Then, in terms of possibilities, it is a field that will never die: people will always need to dress.

EF: Tell us your experience: how was the workshop? What are the main features of the project developed by your group?

R: The title of the project my group developed was “Art out loud!”: an app that would make the visual arts accessible for people not able to see. The idea was that the app could ‘show’ digital material through the comments posted by users in audio note communicate their impressions in front of a work of art. The main objection we got from the jury was that the app was completely free.

E: With my group we have developed an App with the same layout of Tinder, but instead of having to “match” with other people, you have the match with art. The app allows you to easily save images and study your favorite works. It was aimed at making the use of digital data easier and more palatable for anyone.

EF: We are curious about your general impressions on the experience: did you like? Did you find this useful? You can use it in your path of personal study?

R: The workshop came a bit as a surprise, since I had never before come across online archives; in fact, my training does not currently include courses on digital knowledge and archives. The process was quite standard: we divided into groups, in which we discussed ideas about what kind of App we wanted to develop. Among the many ideas, we voted the one that felt more doable, and then got re-divided into new groups, based on the ideas that had received more votes. Into these new groups, we developed the idea and prepared a business plan. All this was then put into a powerpoint presentation we used to pitch our project to potential investors. Even though it was the first time I worked with digital data sharing and working with digital objects, I think that, thanks to my preparation and the courses I follow at Polimoda, I had the right tools to approach the team work. Overall, I haven’t found the experience particularly new compared to what my school offers.

E: Although it had been difficult, at the beginning, to cope with the intricate organisation of such a complex event, I learned interesting things and had an experience that I think will be useful in the future.

EF: As a fashion student, how do you think you might find useful products such as those developed by the various working groups?

E: I believe that not all the projects developed by the groups are closely useful to the field of fashion; still, doing a lot of research is definitely helpful to have a more comfortable and convenient access to all the content of Europeana Fashion.

EF: Do you use digital platforms in your creative practice? If so, what and how you use them?

R: I don’t, but it was indeed very interesting to get to know Europeana Fashion and its platform.

E: I use a lot especially Pinterest, for more targeted research; Tumblr, for inspiration, mood and to see a bit of trends. Then there are about thirty less-known websites that I found while looking for different ideas and I like to use. I also check fashion magazines’ websites, they are really interesting.

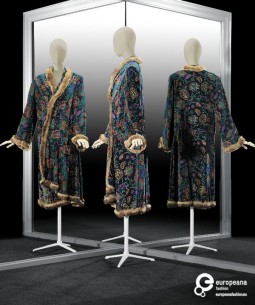

Weawing desire: the alluring fabrics of Bianchini-Férier

Fabric are a mindful connection of threads, composed in almost infinite combinations. Warp and weft can be woven in an almost infinite combinations, with the only exception that at least once, threads must pick. The ability to weave and to connect fabrics, and therefore people and situations, characterized the fascinating history of Bianchini-Férier.

The first pick in a list of woven connections is that of Charles Bianchini, François Atuyer and François Férier. The three, respectively a designer, a technician and a financier, founded the silk factory Bianchini-Férier in Lyon in 1888. The velvets and brocades produced by the Maison obtained immediate recognition and received a silver medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889.

Silk scarf, design by René Lalique on Atuyer, Bianchini, Férier et Cie fabric, ca. 1907. Courtesy Les Arts Décoratifs, all rights reserved.

Although working with the forefront fashion creators, for whom the mills produced, in addition to velvets and brocades, charmeuse georgette and crêpe Romaine, its creative exchanges with artists are however what better describes the prestigious quality of these fabrics.

In 1912 in fact, Bianchini-Férier hired the Fauvist painter Raoul Dufy to design the prints for silks and toiles de Tournon. The artists one year earlier started in a wooden-block printing factory, ‘La Petite usine’, that developed from his collaboration with the couturier Paul Poiret; he continued his activity at Bianchini-Férier through 1932, designing a wide range of patterns, from colourful florals to elaborate scene inhabited by dancers. This experiment, that bound together Paul Poiret, Raoul Dufy and Bianchini-Férier, was one of the first successful collaborations between a designer, an artist and fabric producer.

'Troïka', housecoat designed by Paul Poiret with Bianchini-Férier fabric with print designed by Raoul Dufy. Courtesy Gemeentemuseum Den Haag via ModeMuze, all rights reserved.

Along with Dufy, the silk factory also hired Georges Barbier, Paul Iribe, Sonia Delaunay, Robert Bonfils, Jacques-Henri Lartigue, and later Daniel Buren, among others, to design the prints for its fabrics. This collaborative nature accompanied the Maison in its expansion overseas, when in 1921 the firm opened an office in New York that prevented its recession during wartime.

Silk fabric, print designed by Georges Barbier for Bianchini-Férier, ca. 1920. Courtesy Les Arts Décoratifs, all rights reserved.

Although under another name, the maison continued its activity through the twenty-first century. In the Europeana Fashion collection, it is possible to trace the history of Bianchini-Férier through the creations couturiers realized with these fabrics, ranging from the early twentieth-century designs by Paul Poiret, to a 1960s long dress by Pierre Cardin and a later design by Frank Govers.

Europeana Fashion Focus: Robe Du Soir by Madeleine Vionnet, 1925

The evening dress is made of red silk crepe and decorated with silk threads arranged on top of the basis to create a motif. It was designed by Madeleine Vionnet in 1925.

The dress is sleeveless; it is composed by a basis in plain red silk, and its particularity lays in the decoration, which is applied on top of the silk basis. The way the silk threads are arranged creates a motif that reminds of ancient Greek patterns. In being loose on top and more fitted from hips downwards, the decoration itself becomes structural, moulding the entire silhouette.

The dress has all the iconic details that identify 1920s party style: lowered waistline, knee-length, flashy decoration. This style was paraded by young and emancipated women called ‘flappers’. The ‘flapper style’ was very recognisable, characterised by a boyish physique and haircut, no corsets, short-fringed skirts and dresses, in vivid colours and embellishments. The style was pioneered by French fashion designers such as Coco Chanel and Madeleine Vionnet, who provided their clientele with creations that responded to the need for a ‘fresh start’ in fashion after WW1.

The object is part of Les Arts Décoratifs Archive. Discover more on the Europeana fashion portal.

Dazzling Couture: Lesage’s Embroideries

‘‘Embroidery is to haute couture what fireworks are to Bastille Day.’ This was the statement François Lesage made when asked about the relationship between couture and his own practice.

When it comes to embroidery, Lesage is probably the first name that comes to mind.Throughout his career, he has collaborated with the most iconic maisons, establishing his reputation of highly-skilled maker and talented creator – or anticipator – of the atmospheres of French couture, and linking is name to the extraordinary details of gowns and accessories. François Lesage was born ‘in the business’: in 1924 his parents had in fact taken over the workshop of the embroiderer Michonet, famous for working, above all, with all the biggest names of French couture. After serving as apprentice in the family business, right at the end of World War II, François Lesage opened a Studio on Sunset Boulevard in 1948, working with costume designers in the film industry. However, the sudden death of his father made him decide to return to France and take the role of director of the atelier.

In many ways did Lesage highlight the duplicity of his practice: between craftsmanship and invention, technical savviness and exquisite taste. His role as ‘haute embroiderer’ led him to venture in other fields to inform his practice of innovative techniques that produced never-before-seen effects: he was also an inventor, experimenting with dyeing techniques and stitches. An outstanding number precious materials were used to create the samples: sequins, feathers, chenilles, ribbons, buttons together with unexpected materials, such as Rhodoid. , Elsa Schiaparelli and Yves Saint Laurent are said to have worked only with him, trusting not only his ability but, above all, his talent in predicting what they wanted to complement their creations.

François Lesage developed collaborative relationships not only in France, but across the international scene: Pierre Balmain, Cristobal Balenciaga, Christian Dior, Jacques Fath, Jacques Griffe, Jean Dessès, Hubert de Givenchy, and, from the 1980s on, Oscar de la Renta, Bill Blass, Geoffrey Beene. Karl Lagerfeld, who had just arrived at Chanel, began a professional relationship with him 1983, opening a new era for the maison: Mademoiselle Chanel in fact had never wanted to work with him before, given the strong link he had with rival Elsa Schiaparelli.

At the end of the 1980s, François Lesage was celebrated with a travelling exhibition first held at the Palais Galliera in Paris, then at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, the Fashion Foundation of Tokyo, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. During his life, he received numerous awards and recognitions, such as the Medal of the City of Paris in 1984, and the Grand Prix de la Création of the City of Paris. He was made a Knight in the Order of the Legion of Honor, and was later promoted to the rank of Commander in the Order of Arts and Letters.