Archive for October, 2016

Europeana Fashion Focus: Dress by Charles Worth, ca. 1882

Dress by Charles Worth, ca. 1882, Courtesy Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin CC BY NC SA

The dress is made of blue velvet, with a delicate floral pattern in different nuances of yellow, and lined in honey-coloured satin silk. The front presents a cascade of lace ruffs, The collar and the sleeves are also finished with silk ribbons and lace. It was designed and produced by the Maison Worth in Paris, around 1882.

The dress is a quite typical example of 1880s fashion: the skirt is quite flat and narrow on the front, enriched by a luxurious lace garniture; the back is very voluminous and its construction is highly elaborate, with folds piled one upon the other to emphasise even more the shape of the silhouette.

The peculiar shape of the dress is commonly known as cul de paris (Paris Bottom), indicating the provenance of this fashion. The cul de paris was made possible by the tournure, a device that was to be worn underneath the skirt, emphasising the backside. It was very popular in the years between the 1870s and the 1880s, and its form evolved throughout the period: from a horsehair-filled cloth to a highly technological wire contraption that followed the movement of the body.

The dress was designed by Charles Frederick Worth, who is considered to be the father of Haute Couture. Born in England, he got his fame in Paris, where he established his fashion house in 1858. He contributed to the establishment of Paris as cradle and capital of couture. Amongst his clients many European royals are remembered, the most prominent being Princess Eugenie and Princess Elizabeth of Austria; he also used to dress actresses, such as Lilli Langtry and Sarah Bernhardt, both on and off the stage.

The object is part of Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Discover more on the Europeana fashion portal.

The ‘Casacca’: Unisex by Emilio Pucci

Celebrated as ‘the king of prints’, Florentine designer Emilio Pucci was not only a master of the decorate surface. Instead, the experimental nature that he expressed through his prints was as effective in volumes and shapes as in the bright colours and patterns he designed.

Since the opening of his shop ‘La Canzone del Mare’ on the island of Capri in the early 1950s, the Marquis Emilio Pucci designed sportswear pieces for the jet set celebrities visiting the international resort during the good season.

The 'casacca', or short tunic, designed by Emilio Pucci, 1950. Courtesy Emilio Pucci Archive, all rights reserved.

Though the vibrant colours of his fabrics – inspired by the natural environment of the island and its waters – may suggest a radiant femininity, his iconic Capri pants and shirts were drawn from the male wardrobe. Exemplifying the ease of the island life, his shapes were rather linear, such as in the case of his iconic ‘casacca’.

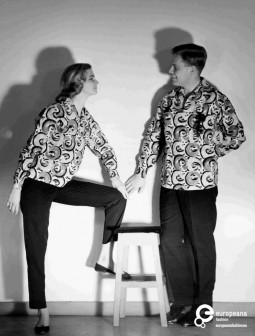

Models wearing the 'casacca' printed with the 'Riccioli' design, 1957. Courtesy Emilio Pucci Archive, all rights reserved.

The ‘casacca’, or short tunic, had since been a recurrent element in his collections. Romantic in its idea and reminding of both the simple clothes worn by the island fishermen and women and the styles of the Florentine Renaissance, the ‘casacca’ is composed by two straight panels with short tears on the sides, sleeves of variable length and a swan collar, usually worn folded.

Two models wearing the 'casacca' printed with the 'Onda' design, 'Palio' collection. Courtesy Emilio Pucci, all rights reserved.

The a-gendered line of the tunic, to be worn with the narrow Capri trousers, had been thus exasperated in some rare menswear experiments of the designer. In the late 1950s, for example, male and female models were portraited wearing the ‘casacca’ in the same style and prints, with black trousers and shoes. Though a-genderism and unisex themes might have been distant from the romantic vocabulary of the designer, these designs highlight the modern sensibility that surrounded the exceptional work of Emilio Pucci.

Discover the Emilio Pucci’s ‘casacca’ in the Europeana Fashion collection.

Vestirsi da Uomo: performing masculinity at Pitti

For its 80th edition in 2011, Fondazione Pitti Discovery launched ‘Vestirsi da Uomo’ (Dress like a Man), a project focused on the exploration of the meanings and definitions of contemporary masculine elegance. To mark this event, both in 2011 and 2012 Pitti Discovery presented a reading of the theme which took the form of two highly reflective and striking performances, which played around the idea of gender being something performative and performable.

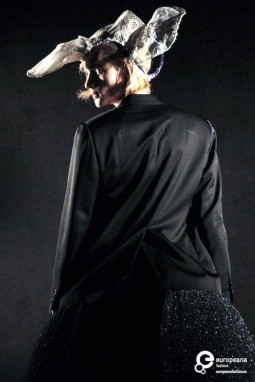

Vestirsi da Uomo, performance curated by Marc Ascoli featuring students from Polimoda, Pitti Uomo 81, 2012, Courtesy Pitti Immagine, All Rights Reserved

In 2011, Olivier Saillard was appointed as the director; as historian and curator, he gave an original interpretation of the theme and developed it ‘on the catwalk’: female models – the iconic mannequins Violeta Sanchez, Amalia Vaireli, Axelle Doue’, Claudia Huidobro – were in fact walking down the runway ‘wearing’ what Saillard defined as ‘masculine attitude’: a way of being and dressing, which comes before the gender we commonly attach to each piece of clothing.

Vestirsi da Uomo, performance curated by Olivier Saillard, Pitti Uomo 80, 2011, Courtesy Pitti Immagine, All Rights Reserved

The following year, in occasion of Pitti Uomo 81, the second edition of Vestirsi da Uomo took place. Art director Marc Ascoli staged this edition; he developed his concept on the idea of the gender game; as he himself declared: ‘a game between real and surreal, between the real garment and the imagery it evokes: exuberant, filled with energy, fanciful, dreamlike and visionary.’ Ascoli decided to involve students from Polimoda to take part onto the performance, considering them as the new generation shaping the contemporary sensibility towards fashion and clothing, and how they can help in shaping identity.

Vestirsi da Uomo, performance curated by Marc Ascoli featuring students from Polimoda, Pitti Uomo 81, 2012, Courtesy Pitti Immagine, All Rights Reserved

The two performances demonstrated how, in a society in which the very definition of gender has become fluid and evolving, contemporary masculinity can be regarded more as an attitude than an actual apposition related to men. In this scenario, fashion plays a fundamental role, not only because clothes visually gather the characteristics that we appoint to what is masculine or what is feminine, but also because clothes, and the way they are constructed, can influence postures, gestures and, consequenty, behaviours.

The Riding Attire: a history in-between the genders

The influence riding attires have had on the development of new trends in clothing is undeniable, at least if we consider western fashions; this happened because horses have been one of the main mode of human transportation throughout many centuries; horse riding initially developed as a male setting, while women were obliged by etiquette to the sidesaddle for a long time; this division though didn’t stop the two attires – masculine and feminine – to share many similarities.

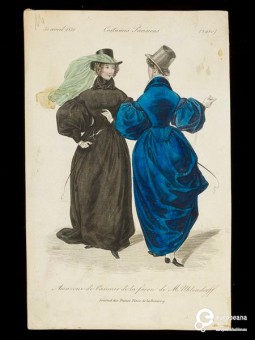

The most important features of riding costumes were comfort, protection against any weather condition and fabrics of a good quality that assured resistance and durability – all elements that were highly valued in the male dressing code as well. A formal habit for riding sidesaddle was finally recognizable since the mid-17th century. It was composed by a more ‘masculine’ top and a feminine bottom: a tailored jacket with a long skirt to match, a chemisette and a hat, in the formal men’s style of the day. The ensemble was completed by low-heeled boots, gloves and a necktie.

On the contrary of the most costume changes of that period, usually influenced by France, the equestrian fashion had been leaded by England, because of the long tradition of sports involving horses and by the members of British Aristocracy, who used to spend much time in the countryside, practising hunting. Several accessories were introduced among them, giving structure to a real language and originating a sort of code: for instance a red jacket with black velvet collars signaled an experienced foxhunter. Their habits influenced other countries´ fashion, as France, which adopted the traditional frock coat cut just above the knee, changing its name from “Riding coat” to “redingote”.

During nineteenth century, the general equestrian fashion toned down. Tailors started to make the equestrian clothes, for both women and men. Towards the mid-nineteenth century, riding became a common habit for the upper-middle class and the equestrian clothes became fashionable dress as well. Worn as informal day wear for traveling, visiting, or walking, they were less elaborate and the colours were darker than before. Also, for the first time pants were introduced for women to ride in, worn under skirts at the beginning. Both male and female riders used tweed jackets for hacking. In the beginning of the twentieth century women started to riding horses astride, breaking a long tradition. With a huge symbolic impact, this changed their habits in costume and society: from then on, more and more women rode without skirts and just wearing trousers.

When the industrialization and transport revolution introduced trains and cars, the use of horses changed and riding became just linked to sports and free time; however its influence on fashion was not over. Even today the country elegance of riding attire is still inspiring fashion houses such as Ralph Lauren and Gucci, who have their own equestrian line.

Discover more amazing pictures of riding attires on Europeana Fashion portal!

A Madame of Couture: Louise Chéruit

Since Charles Frederick Worth established his eponymous fashion house in 1858 and introduced the figure of the ‘couturier’ as it is known today, male dress-makers imposed their own idea of femininity over the female body. However, since the late nineteenth century, women’s started establishing prestigious couture houses that challenged those of their male colleagues. Among those, the couturiere Louise Chéruit.

The Chéruit atelier, directed by Louise Chéruit herself, occupied the hôtel de Fontpertuis in Place Vendôme, the same which would have been acquired by Elsa Schiaparelli in 1935. One of the most celebrated couturiers of her time, she was also one of the first supporters of Paul Poiret, whose sketches she bought in 1898.

Louise took over the seventeenth century hôtel de Fontpertuis in 1906, as a result of her and her sister Marie Huet increasing success inside the house of ‘Raudnitz & Cie’, which previously occupied the building. ‘Raudnitz & Cie’ was founded in the 1870s by Ernest Raudnitz and his sisters, who later directed the Maison when their brother left them in 1883 to open his own. There, Luoise and Marie trained themselves since the 1880s and saw, by 1900, their names sewn in the dresses labels of the maison. When they took it over, it counted one hundreed employees.

Woman in a dress by Chéruit, photo by Félix, ca. 1912. Courtesy Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC BY NC SA.

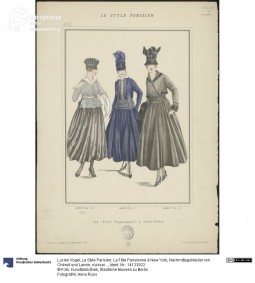

Remembered in Marcel Proust’s ‘À la Recherche du Temps Perdu’, as one of Parisian greatest couture houses, the creation of ‘Chéruit’ maintained a traditional femininity. In 1911, the maison also presented the ‘pannier gown’, inspired by the eighteenth century lines and volumes. In 1912, the press acclaimed Louise Chéruit, whose figure was drawn by the most fashionable artist of her time, among them her alledged lover Paul César Helleu, signed a collaboration which Lucien Vogel, which resulted in the prestigious fashion magazine ‘Le Gazette du Bon Ton’, a priviledged medium of promotion of French couture.

'La Fête Parisienne à New York' in 'Le Style Parisien', two afternoon dresses by Chéruit and one by Lanvin (in the middle), by Lucien Vogel, 1915. Courtesy Anna Russ, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC BY NC SA.

While the Maison ‘Chéruit’ continued its activity all through 1935, Louise Chéruit left the house in 1923, when her conservatist vision could not meet the needs of the exuberant flappers of the 1920s. The maison was acquired by Mesdames Wormser and Boulanger in 1915, after Luoise Chéruit incurred in a scandal which involved her lover, an Austrian noble and military officer, accused of being a German spy. The rumors, which also asserted that she would have been a spy herslef, impaired her celebrity, leading her to decline. Before closing in 1935, however, the maison was even mentioned in Evelyn Waugh’s bestseller ‘Vile Bodies’, published in 1930.

Discover the creations of Chéruit in the Europeana Fashion archive.

The vest: a men’s charm

A vest is defined as a sleeveless garment covering the upper part of the body. Its name derives from French veste, meaning ”jacket, sport coat”, Italian veste ”robe, gown”, both coming from the Latin vestis. Later it took the name of “waistcoat”, derived from the cutting of the coat at waist-level.

Usually worn by men beneath a coat, it has been first introduced by King Charles II of England, who attempted to formalize men’s attire in court after the Restoration of the British monarchy in 1660. We learn it from a diary entry by the English naval administrator and Member of Parliament Samuel Pepys, who on October 8th, 1666, wrote “[t]he King hath yesterday, in Council, declared his resolution of setting a fashion for clothes…. It will be a vest, I know not well how; but it is to teach the nobility thrift.”

However the waistcoat has not been invented in England. In fact it derived from the Persian vests seen by English visitors to the court of Shah Abbas. As John Evelyn, another famous diarist, wrote on October 18th, 1666: “To Court, it being the first time his Majesty put himself solemnly into the Eastern fashion of vest, changing doublet, stiff collar, bands and cloak, into a comely dress after the Persian mode, with girdles or straps, and shoestrings and garters into buckles… resolving never to alter it, and to leave the French mode”.

During the seventeenth century the regular army’s uniforms included waistcoats, which were the reverse colour of their overcoats. At the same time civil people started to wear elaborate and brightly-coloured waistcoats and the trend continued through the eighteenth century too, until changing fashions in the nineteenth century restricted them in formal wear.

The anti-aristocratic feeling after the French Revolution in France influenced the wardrobes of men and women; waistcoats became much less elaborate and their fit became shorter and tighter. The waistcoat moved away from being the centerpiece of a man’s clothing and towards serving as a foundation garment, especially from the 1820s, when elite gentlemen started to wore corsets and the waistcoat, which often had whalebone stiffeners, was used to emphasize the figure.

This fashion remained throughout the 19th century, with less restriction at the waist. Toward the end of the century, the so-called ‘Edwardian look’ made a larger physique more popular.

The waistcoat remained visible in the UK until the late 1960s; since the 1970s it became once again a fashionable and popular garment among businessmen and young people wearing it in ensemble with their suits.

Discover more waistcoats on Europeana Fashion portal!

The Gender of (Fashion) Things

Do objects have a gender? Lately, the question has triggered many of the most cutting-edge and interesting researches within the field of both history and design. When dealing with fashion – a discipline strongly related to the body, as well as to the mind of the wearer – there are many variables that are to be taken into account to try and answer that question.

English fashion plate depicting the Dandy's Toilette, 1820-1829, Courtesy Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC BY NC SA

One of these variables is surely history. Many historical objects are now read as associated with one gender or the other, even though a closer look might turn the perspective upside down. One of these objects is the corset: even though contemporary narratives describe the corset as a device for female seduction, corsets weren’t just used by women to shape their silhouettes. Since posture and shape were incredibly important element in men’s appearance, in nineteenth century busts and corsets for men were produced, advertised and sold – and taken up, among others, by the most fashionable dandies. Also, man’s corsets show how considering different geographies can change the perception of the ‘gender’ of some objects.

Another aspect to be considered is the ‘look’, the appearance of the object, which associate them with a precise gender identity. Jewels and other elaborate accessories, as pins and buttons, above all the most lavish and flashy, are generally associated with women. Also bags – above all clutches and purses, which developed from the minaudiere and the ridicule – have been appointed as something ‘feminine’. Both these categories of objects seem to have a gender of their own, defining the gender identity of the user more than being defined by it. Since some objects are so linked to one gender or the other, they have been used to go against the status quo and protest the social rules of conformity: this is what happens in the 1970s, when men’s jackets and other items were worn by women to go against the patriarchy and challenge both existing social structures and roles.

Pair of man's silver waistcoat buttons, decorated with filigree and coloured pastes, Sweden 19th century, Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, CC BY SA

To conclude this short overview, it seems that the very core of the matter can be seen in the encounter between the ‘pure’ object and the user. As Pat Kirkham points out, sometimes the apparently ‘un-gendered’ objects are added some elements in order to become gendered, and automatically signal the identity of the wearer: for example, unisex shoes as Doc Marten are ‘feminised’ with girly laces. To answer to the pending question ‘are objects gendered?’ we have to take into account the active role of the user in the process of giving meaning to an object, whose gender is not only defined by its design and function, but above all by who uses it and how – which can sometimes change the very nature of the object itself, subverting its traditional role it was given by society.

Europeana Fashion Focus: Swing coat by Jacques Fath, ca. 1950

Swing coat designed by Jacques Fath, ca. 1950. Courtesy MUDE - Museu do Design e da Moda, all rights reserved.

The coat is made in wool gingham fabric, in the colours of black and white. It’s a typical example of the kind of outerwear that was fashionable during the 1950s, with its abundance of fabric and volume, which is a feature of the iconic silhouettes of those years. It was designed by the Parisian couturier Jacques Fath in the 1950s.

The long coat is open at the front and presents no buttons, except for two button-holes on the shawl collar, which is unfolded to show the precious black lining. The cut of the shoulders is slightly low and the wide sleeves end with black cuffs, made of the same fabric of the collar. The coat is bell shaped and its volume is given by the wide folds that go from the bust to the bottom hemline.

Jacques Fath was, along with Christian Dior and Pierre Balmain, one of the couturiers who reinstituted the epitomized idea of feminine beauty after the end of World War II, characteristically represented by the New Look introduced by Dior in 1947. Heir of a creative family, he was a self-taught designer who got his knowledge of the history of costume in museums and books. He opened the ‘House of Fath’ in 1937, where later he employed as his assistants Hubert de Givenchy, Guy Laroche and Valentino Garavani. After his first successes in 1940, he developed strong relationships with many illustrious clients, including Greta Garbo, Ava Gardner, Evita Perón and Rita Hayworth, who chose a dress created by him for her wedding to Prince Aly Khan. His house closed in 1957, three years after the death of the couturier.

The object is part of MUDE – Museu do Design e da Moda archive. Discover more on the Europeana fashion portal.

No Gender in Space: Unisex in the 1960s

The 1960s were a time of innovation and exploration: while science ventured into space with a series of missions culminating, in 1969, with the Apollo 11 touching ground on the Moon, fashion foresaw a cosmic-broad future, experimenting with new technologies and fabrics, and introducing unisex silhouettes.

Predicting the woman of year 2000, the ‘Space Age’ designers Pierre Cardin, André Courrèges, Paco Rabanne and Rudi Gernreich designed sleek, colour neutral silhouettes in plastic materials, accessorised with vinyl boots, helmets and plastic googles. Though contemporary history shows that their prediction might not have been that accurate, their creations influenced fashion for the next decades.

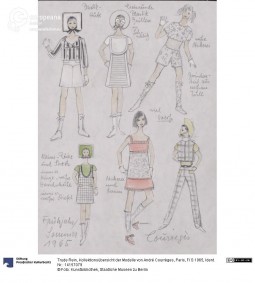

'Collection Overview' of the models presented by André Courrèges, S/S 1965, sketches by Trude Rein. Courtesy Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC BY NC SA.

While the ‘Space Age’ is considered to start with the launch into space of Sputnik in 1957, the first artificial Earth satellite, the ‘fashion Space Age’ instead is a trend that originated on the Parisian catwalks in the early-1960s; during this time, Italian-born fashion designer Pierre Cardin and French André Courrèges, off from their carriers in French couture houses, decided to launch their futuristic lines. Along with them, Paco Rabanne and Rudy Gernreich contributed to the construction of a defined imagery both with their fashion and costume designs, that include the iconic creations for ‘Barbarella’ (1968) by Rabanne and, later, ‘Space: 1999’ (1975-1977) by Gernreich.

Man's ensemble 'Cosmos', designed by Pierre Cardin, 1967. © Pierre Cardin. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, CC BY NC.

Inspired by the youthful wave that defined those years, these designers focused on the exploration of the new potentialities of dress, moving away from the past to look forward to a romanticized future. In 1963, ‘Cosmocorps’ collection by Pierre Cardin introduced new shapes and geometries, adopting in some cases the same cuts, colours and fabrics for the creations for both men and women. Similarly, since 1961, André Courrèges infused in his modern collections a sense of gender neutrality, drawing elements from children clothes. In addition, their shared characteristic of experimenting with new materials let their creations free of historical gender associations.

Women's ensemble, designed by Pierre Cardin, 1965-1970. Courtesy Modemuseum Hasselt, all rights reserved.

Their designs, however, mostly reworked womenswear with masculine elements, sometimes even making the sex of the wearer more obvious – something that was shared also by the unisex trend originated at the same time. In fact, although they aimed to cross the gender lines, the neutral cuts of unisex clothes emphasized the body of their wearer, enhancing instead of blurring its sexual identity.

Discover more creations of the ‘Space Age’ fashion designers and of the unisex trend on Europeana Fashion.

Giorgio Armani: Questioning Gender

When thinking about how fashion has contributed to the debate concerning gender identity, it is possible to pinpoint a tradition of designers who have constantly questioned the very meaning of the idea of gender, while basing their aesthetic choices on their own definition of masculinity and femininity; Giorgio Armani is surely on of the most prominent representatives of this flow.

Starting his career as fashion designer in the years between the 1970s and 1980s, Mr Armani developed his aesthetic language blurring the boundaries between what was allowed to each of the sexes, redefining with his designs the very meaning of what is masculine and what is feminine. His ensembles – made iconic also by the infamous advertising campaigns, which were constructed on the very idea of gender bender and denial of stereotypes – seemed to be the natural response to to a shared feeling that permeated society in those years of political and social turmoil; women were beginning to ask recognition in the workplace, campaigning to be rightfully considered leaders; men, on the other hand, were starting to openly explore their sensibility, not being afraid to show it on the outside.

Exhibition 'La Regola Estrosa: Cento anni di eleganza maschile italiana’ held at Pitti Uomo 44, 1993, Courtesy Pitti Immagine, All Rights Reserved

Mr Armani’s replied to these changing sensibilities with two silhouettes that were coming directly from the attentive observation of the world around him, applying his innate ability to detect the requirements of a society in total revolution. Men’s jacket were stripped of their structure and inner paddings, allowing freedom of movement and giving a relaxed flair to the – rather formal – classical masculine attire; while women could pick from a varied set of structured garments, mostly jackets with big padded shoulders and sharp lapels – which could either be paired with streamlined trousers or flouncing printed skirt: in Giorgio Armani’s view, women didn’t have to completely renounce to frills and to the plasure of ornamentation, but finally gained the freedom to play with different styles, juxtaposing diverse attitudes and tastes to re-create, in their outfit choices, their unique personality.

With his designs, Mr Armani has reflected on both female and male identities, developing two similar but intrinsically different ideals: in this way, he has been able to talk to a wider audience, made up of men and women who were gaining confidence in being complex and, in their complexity, not only contemporary, but more precisely postmodern.