Archive for September, 2016

The Uniform, Irony and Eroticism

Uniforms stand at the meeting point between fashion and power. With their ability to define roles, in particular contexts their importance reaches a different level – above all when irony and eroticism get involved, contributing to their timeless appeal.

The strong relationship between fashion and power – two defining forces of our society - is especially felt when considering uniforms. These garments summarise both the striving contrast of appearance and identity, in their being neat and precise; yet, they hide the wearers own identity behind a role that takes form with the shapes, the colours and the accessories constituting the uniform itself.

'Varieté-Kostüm: Liftboy', drawing by Herbet Mocho, ca. 1925. Courtesy Dietmar Katz, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC BY NC SA.

In this sense, these elements hold a special place in comical representations, plays and caricatures. Extremely exaggerated or reduced, they help to visually render a particular aspect or fault of what they stand for. A bigger lapel may recall the lust for badges or decorations, a looser fit a certain lasciviousness, inflated details a symptom of frivolousness.

Dancer in 'Varieté-Kostüm', drawing by Herbert Mocho, ca. 1925. Courtesy Dietmar Katz, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC BY NC SA.

As they serve to represent a precise character in society, thus in this sort of ironic and satirical representations to precise uniforms are attributed precise roles, portrayed by both men and women. In this kind of shows at varieté theatres and cabarets that the erotic connotations attributed to uniforms took form: daring costumes were worn by dancers and performers, deliberately to get the audience to laugh at them.

These connotations still complete the imaginary that surrounds uniforms and contribute to their fascination. Instead of corrupting their power, irony and eroticism help constructing their popular identity, from which fashion draws constant inspiration.

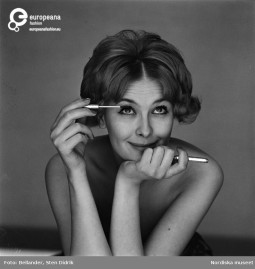

Written on Her Face: the Power of Make-Up

Uniforms can come under any form and aspect, and serve as devices to create the image of ourselves we want to put forward. This is particularly true for everyday, personal uniforms – what we decide to wear in order to ‘be’ the person we want to be. Amongst the many kinds of uniform that we might think of, surely make up holds a special place, since it sits between the idea of something ‘disposable’, which can be put on and off, and that of something so necessary to become natural – and simply unavoidable.

Trends in make up – as the parameters of beauty – have shifted throughout time and space but, in the Western world, it is especially during the twentieth and nineteenth century that their popularity has grown. At the beginning of 1900, a pale complexion was a must amongst rich and educated people, because this differentiated who didn’t have to stay out in the sun to earn a living from the people who had to work. Compacts containing power were then one of the only objects associated with make up that was appropriate for women to carry around; some of them were very elaborate, as pieces of jewellery, and enriched with initials or incisions.

During the 1910s, make up was not popular, since it was associated with prostitutes; it’s probably with the rise of popular icons, whose image served as model to shape tastes and form styles, that make up really took off both on the market and in visual culture. So, together with their outfits, the make up of the likes of Greta Garbo, Ava Gardner, Audrey Hepburn, became a fixed feature of their age, necessarily weighed on the development of new items and the diffusion of different products. Mascara, for example, was firstly invented by Eugene Rimmel in 1913, while lip gloss was introduced by Max Factor in the late 1920s, but the popularity of these products came with the use by actresses on the big screen, and also by rather strong marketing campaign based on the benefits women would get by using make up regularly.

Interestingly, the history of cosmetics is linked to two incredibly savvy businesswomen. Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden, always depicted as opponents in the market, share the merit to have established the use of cosmetics as not only proper, but also necessary to the appearance of a woman. Helena Rubinstein marketed the mascara and made it very popular, while Elizabeth Arden used her advertising to talk to women to convince them that being beautiful – at every age or class – was synonymous with being appropriate, and thus, at least in Arden’s view, powerful.

Scouting for a Restyle: Designing Uniforms

In 1980, the uniform of the Boys Scouts of America had a restyle. Its previous militaristic look, which hadn’t received a complete overhaul in over sixty years, had been reinterpreted by no other than the infamous fashion designer Oscar de la Renta.

Founded in 1907, the Scout Movement is a youth organization that welcomes boys and girls worldwide, supporting and educating them during their youth years through a program focused on practical and outdoor activities. Outdoorsman Dan Beard and illustrator Ernest Thompson Seton were the credited designers of the first uniform of the Boy Scouts of America in 1910. The uniform, ideated to promote equality among the movement members, is regarded as one of their characteristic elements, along with the handkerchief and campaign hat, the fleur-de-lis and the trefoil, the badges and patches.

'Escoteiros de Portugal', boy scout uniforms, designed Ricardo Falcao and Lito Lusitana, 1936 ca. Courtesy Museo del Traje, all rights reserved.

It took two years for Oscar de la Renta to finalize the reinvention of the Boys Scouts of America’s uniform. When he was asked to design the uniform in 1978, the Dominican fashion designer had to confront with many rigid criteria, most importantly with those of durability and easy care. The most noticeable changes the designer introduced in the uniform regards the two-tone colour scheme for the Boy Scouts and the adult Scouters; he abandoned the khaki green for a khaki tan shirt, paired with drab green trousers, both pieces made of polyester and cotton.

The designer also took functionality into account: the shirts collars could be turned down when wearing handkerchief and epaulets were added to the shoulders to make easily identify the program division. Large cargo pockets, useful to store vital possessions, were added to both trousers and shirts. For thirty years, from 1980 up until 2008, the uniform designed by Oscar de la Renta had been worn by millions of American scouts.

Differently from the fashion designers’ common use of historical uniforms as references to implement or develop their collections and express their own design grammar, Oscar de la Renta blended his own point of view on fashion and clothing with the values of the movement itself; the result was a new uniform that represented the history and social values of the institution.

Small but full of pride: pins and badges as uniforms

In the rush of everyday life, most people may refer the act of dressing ‘unconscious’, considering it a routine activity that does not require a high level of attention. Surprisingly enough, the details – and thus the smallest objects – are the one requiring the biggest effort, since they have the power to become ‘wearable statements’ – which makes them real uniforms.

This is true for those objects that were created especially to signal some kind of belief, political affiliation, or support to a cause. Badges, pins and insignia have the power to subvert the meaning of a dress, becoming themselves a uniform on their own right; they can convey messages and meanings that a whole attire would represent. Badges rely on the striking visual power of their design to separate who wears them to ’the others’. Within the military – one of the environments in which these kind of objects are more valued – pins and badges are often given as prizes, recognitions of honour and pride. The symbolic value of the badge is enhanced by ceremonies organised precisely around the act of ‘decorating’ a person with a quasi-sacred object. Badges can also offer comfort to those wearing it, because they define, to themselves as well as to the others, what they stand for, and thus serves as sign of belief and ultimately, of identity.

Maybe these senses of ‘pride’ and of ‘comfort’, of which badges are usually infused, are what led to the use that the LGBT community has been doing with objects of this sort – be it badges, pins, or other ’symbols-to-wear’. The gay community has depicted its icons – the ones that formed its vocabulary and then its visual identity – on badges and pins that are worn not only by members of the community itself, but also by supporters and, more broadly, by people sharing the values of emancipation, equality and liberty. The most famous symbol is surely the rainbow flag, created in 1978 by the American artist Gilbert Baker as a symbol of diversity, respect and tolerance. This symbol has been translated into pins and other objects, building a common language for an incredibly diverse group of people, coming from different geographies and social classes.

The badges shown in this post were produced and used during the Stockholm Pride in 2008, year in which Stockholm also hosted the Europride Festival, presenting itself as the international capital of freedom and social progress. Nordiska Museet holds a complete documentation of Europride/Stockholm Pride 2008, with interviews, photographs and objects, including articles about the different social services that participated in the Pride celebrations: an amazing project of ‘archiving the present’.

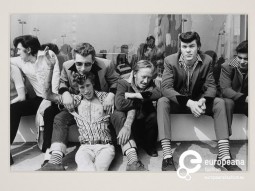

Teddy boy – wearing a uniform to be different

Teddy Boys -dressed with long, narrow lapelled, waisted jackets, narrow drainpipe trousers, ordinary toe-capped shoes and a fancy waistcoats – were one of the first youth groups to differentiate themselves as teenagers, weighing in the emergence of a youth market.

It was the late 1940′s when Savile Row Tailors attempted to revive the styles of the Edwardian era (1901-1910) into men’s fashion, shaping a new style, which was primarily addressed to the young, aristocratic ‘men about town’. Additionally, barbers began offering individual styling. Around 1952 this style spread out and reached young working-class males who, despite their gentleman appearence, quickly became associated with trouble on newspapers and by media in general. As a result, the middle class felt that they could no longer share the style with its new adherents.

'Group of Teddy boys - Southend on Sea', 1974. Photograph in black and white by Kevin Lear. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum. ©Kevin Lear CC BY NC

Wearing the Edwardian style was a conscious attempt to rebel against the grey austerity that had enveloped the country after the war, as well as a way for teenagers to differentiate their clothes from those of their parents. These fashionable young men, descending at the same time from the upper-class Edwardian dandies and the older delinquent subculture of South London, initially simply known as Edwardian’s, would later be called Teddy Boys.

Woman's trouser suit in red and black velvet, Teddy Boy styling, designed by Lee Bender for Bus Stop in 1972 and made in 1993. England. Courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum. ©Lee Bender for Bus Stop CC BY NC

The term “Teddy Boy” was coined on September 23rd 1953 by a Daily Express newspaper headline which shortened Edward to Teddy. It is also known that the girlfriends of working class Edwardian’s were referring to them as Teddy Boys before. Less known then Teddy Boys, Teddy girls were working class teens as well, who would dress up in their own drape jackets, rolled-up jeans, flat shoes and tailored jackets with velvet collars.

In 1958 a huge Italian influence on fashion signed the begining of the end of the Teddy Boy as a mainstream style. However, there continued to be a genuine revival of that style through the 1970s, even if the movement lost its roots and the trend started to be associated with Rock’n’Roll and the emerging interest in Rockabilly music. During this period the look was adopted by Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren through their shop ‘Let it Rock’ on London’s Kings Road and it was a mid step to move on to other styles such as the Punk and Rocker styles.

Discover more interesting pictures on Europeana Fashion portal!

Europeana Fashion Focus: Ensemble by Yohji Yamamoto, A/W 2000/2001

The outfit is composed by a hooded jacket and a long skirt. Both pieces are in cashmere wool, and present different patterns, recalling traditional Indian designs; the finishings are in coyote fur. It was part of autumn/winter 2000/2001 collection by japanese fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto.

The jacket is short and fitted, with no collar, and closes on the front with a safety-pin. The sleeves are made of a single layer of fabric, and on the left sleeve is a label with an Indian motif. For the jacket two materials have been used: a wool fabric with woven cashmere motifs in salmon, gray, green and red, and a silk twill in plain beige-gray. A silk and cashmere hood, lined with coyote fur, is attached to the jacket with four buttons. The full, A-line skirt is made from the same cashmere fabric of the jacket, and lined inside with silk twill. Between the two layers of fabric there is an inner layer, made of polyester, which makes the skirt flared. The waist is also trimmed with coyote fur.

The outfit was designed by Yohji Yamamoto, as part of his A/W 2000/2001 collection. The japanese designer joined together suggestions from different populations, reflecting on their clothing habits, linked to traditional techniques and materials; from India to Mongolia and North America, the influences draw trajectories and reflect on how people in different countries and contexts respond to the environment, keeping up with nature and its variations. The collection fits coherently in the creative view of the designer, who favours oversized volumes, thick fabrics and unexpected materials; it also seems to show how clothes can protect and, at the same time, be a symbol, declaring the identity of the wearer through patterns and cuts; these elements together recall peculiar traditions and customs of a precise place, and associate people, in their instinctive behaviours, across the world.

The object is part of Centraal Museum Archive. Discover more on the Europeana fashion portal.

Neat and Tidy: the Housemaid Uniform

That of the housemaid was the second largest category of employment in Victorian England. A position developed in the rigid and articulated structure of domestic work, it was defined by strict rules, customs and a proper costume.

In its commonly recognized version, composed of a dark dress, a white collar, apron and headband and dark shoes, the housemaid uniform finds its origin in the Victorian era. Before, it was not common for maids to wear a particular uniform and, while male servants used to wear a livery, girls often wore their mistresses’ old clothes. This sometimes led to embarrassing confusions between the maid and the mistress, a common theme in the 18th century drama.

'Le Nettoyage', a maid and a servant cleaning up a room; 1876/1920. Courtesy MoMu - Fashion Museum Antwerp, all rights reserved.

It was in the Victorian era in England, a period characterized by a strict class differentiation, that housemaids were first assigned a distinct uniform, that helped to recognize her position and role in the house. Since the maid represented the household, neatness and tidiness were the keywords of her costume. Precise rules were set that imposed the maid to change twice a day and, even though the dresses were often handmade or purchased by the maids themselves, they respected shared norms and trends, dictated by fashion and, of course, by the mistresses as well.

Apron, headband, cuffs and collar, part of a housemaid uniform, 1920/1930. Courtesy MoMu - Fashion Museum Antwerp, all rights reserved.

In the morning, when the maid was supposed to do the harder jobs, she would wear a plain gown in washable materials with a white bib apron and shoulder straps, while during the afternoon she should wear a black woollen dress with white linen collar and cuffs, and a withe apron. All through the day her hair would be protected by a white headband tied with black ribbon.

Even if housemaids were depicted in paintings and illustrations, it was only in the 1920s that garments manufacturers started to produce ‘fashionable’ housemaids’ dresses in a variety of fabrics; uniforms even started being featured in advertisement on ladies’ magazines. It is through these paper materials that the memory of the housemaid dress survived, as its practical nature mainly prevented the dresses to be preserved; the remaining examples, now kept in museums and archives, still are important witnesses of a wider dress – and social – history.

School Uniforms

The historical origins of school uniforms are to be found in 16th Century England, when uniforms were first instituted at a charity schools for poor children, in part to recognise them and also because it was easier and cheaper then to buy standardised clothes.

It was not until the nineteenth Century that the great English public schools began using uniforms. School uniforms have been less common in the rest of Europe, where for many years they became associated with children from ealthy families attending exclusive private schools. There are a lot of documents suggesting that school uniforms were worn in the nineteenth century in other European countries, but there are few information on these uniforms and how widely they were worn. Many of them were based on military styles.

A photo of 'Athena' high school students in the national-day parade. Athens, Greece, 1952. Courtesy Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation.

In Greece, the school’s costume codes were primarily dictated by the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, through a series of circular decrees sent to all public schools as internal measures of civil organization. Even before War World II, and until the 1970s, the individual boards of Greek high schools held frequent sessions to further discuss these decrees and formulate decisions on the costume and social behaviour of the students.

During this period, school uniforms for female pupils consisted mainly of plain cotton pinafore, while boys were obligated to wear a hat called pilikion, characterized by blue color and an emblem of a owl. Similar to a Police Cap and worn even outside school, it was the most important boys’ school garment for many years.

Elementary school children, both boys and girls, wore smocks for many years as a national requirement, although actual enforcement varied. The smocks were mostly blue with wide white collars.

Dark blue felt cocked cap banded with blue ribbon with embroidered "Κιλκίς" (Kilkis) and two Greek flags. Two bands with free edges at one side with embroidered emblems. Cotton fabric lining and brown leather sweatband. Tripolis, Greece, twentieth century. Courtesy Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation, all rights reserved.

The costume code rules were more rigorous in private schools from the 1950s onwards: the school uniform became a sign of severity and status. The colours were usually blue and white. The white detachable collar was another indispensable component of the school dress, which was not mass produced, but sewn at students’ home. Girls in public schools, on the other hand, wore black uniforms. Every students wore the emblem of their institute in a form of a cockade or as embroidery.

The school uniforms, seen as emblems of modesty, virtue and external equality among pupils by the past generations, has been abolished from public schools in Greece since 1982. However, even after the fall of the dictatorship similar decrees were issued by the Ministry and addressed to the female students, who were invited to adopt ‘non eccentric hairstyles and use of blue knee lenght uniforms with a white collar’.

During the late 1970s, famous fashion designer Yannis Tseklenis created special school uniforms designs for the more affluent students.

The pictures in this post belong to the Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation. Discover the entire selection on the Europeana Fashion Pinterest page and browse more images on the Europeana Fashion portal.

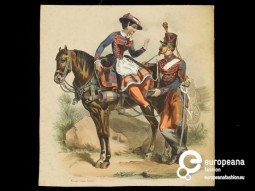

The Vivandières: female protagonists of a men’s world

When we think about the army, what usually comes to mind are images of male soldiers dressed in uniforms, indicating their country, their political affiliation or ideological beliefs. However, the army is a community and, as a diversified and complex community, it is – and was – made up by representatives of both genders, who work together and share spaces, time and, interestingly, style.

Hand-coloured lithograph depicting a soldier and, on horseback, a cantinière of the French Army, Fortune after a drawing by Hippolyte Lalaisse, ca. 1855, Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum CC BY SA

Vivandières – or cantinières – were originally associated with French regiments, but they were present in many different countries as fundamental part of the army. They had several tasks, not only carrying food and drinks to soldiers on the battlefield, but also acting as nurses and supporters of the troops. They were accounted as important members of their regiment, as underlined by historian Thomas Cardoza, who has researched extensively on the topic. Their importance within the environment of the regiment is in some way proved by their ‘official’ appearance – their uniform – which made them more than mere camp-followers, not only participating in the every-day activities of the army, but living the experience as protagonists.

Vivandières’ uniforms were modelled after those of the regiment they served; this tells a lot about how they considered their role, as ‘soldiers’ belonging to the army, whose identity was constructed not only through their occupation, but also through their attire. Their outfit was usually composed by a jacket and a blouse, which could be tight or loose- fitting depending on the regiments they belonged to; trousers could also be either straight legged or full and wide legged, gathered at the ankle or below the knee; a knee-length skirt was usually over the trousers. As for the accessories, they had great importance in completing the look: the most iconic accessory is for sure the brandy barrel, called tonnelet, which was a unifying element in defining the cantinières across different regiments. Vivandières also used to wear hats, either ‘kepis’ or brimmed. Their uniform fulfils two main aspects required to army clothing – and uniforms more generally: it serves as ‘sign’, defining the identity of vivandières as members of a precise regiment, and it is also practical, allowing them the possibility to move and ride more freely than they would do wearing ‘civilian’ female clothing.

Hand-coloured lithograph of a vivandière of the French Army, ca. 1850-70, Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum CC BY SA

At the end of nineteenth century cantinières were forced by regulations to replace their attires with plain grey dresses and metal identification plaques. Despite their popularity, they were banned in 1906 by the French War Ministry. Vivandières’ image anyway remained strongly present in popular culture, theatre, opera and advertising. The Victoria & Albert museum holds a collection of coloured lithographs depicting vivandières in different attires; Browse the Europeana Fashion portal to discover more about this – too often forgotten – feminine presence in what is usually considered ‘a men’s world’.

Between Creativity and Socialism: Aleksandar Joksimovic

Fashion in the era of socialism and the example of the creator explains how the political power, the economic forces and fashion were inevitably connected. After World War II, the Eastern European socialist regimes embraced early Bolshevik ideology, and decidedly rejected Western style of dress. The regimes then had to establish a new dominant style which included practical, simple and classless clothing intended for the working woman.

Dissatisfied with the domestic industry and unfashionable clothes they had been imposed, people turned to private tailors, homemade clothing or to the black market. Soon the country struck a discrepancy between production and consumption. The situation improved in the early 60s, thanks to shopping tours in Trieste, commercial advertisements and, above all, the rise of a new middle class fascinated with Western consumer habits. In all the Yugoslavian territory the desire for individualism was strong, as testified by the articles appeared on the Belgrade newspaper Bazar. The first fashion designer in the Yugoslav territory who directly addressed the need for a change in fashion was Aleksandar Joksimovic.

Aleksandar Joksimovic is one of the most widely known designers in Yugoslavia, not only for his designs, but above all for his ability to conjugate, in his designs, traditions and innovation. Joksimović graduated in 1958 in textile design from the College of Applied Arts in Novi Sad, after a short period studying scenography. After working as designer of work uniforms for the City of Belgrade Institute for Household Improvement, In 1963 he designed his first evening wear collection. His designs received appraisal by the critics, who valued above all his creativity, and this made him a prominent personality in the Yugoslavian fashion system. Joksimović was one of the founders of the National Salon within the institute. In 1964, he started working with the Centrotekstil, Yugoslavia’s export-import giant, but kept his role as ‘couturier’ within the National Salon: his designs were appreciated both by the market and by the political power, since they came from the encounter of fashionable cuts and shapes with traditional motifs and decorations. Joksimović was successful in understanding the social change that was happening in Yugoslavia — and precisely, the needs of the rising middle class – while paying respect to the state ideology, including details from folk costumes in his creations.

Photograph of the Damned Jerina (Prokleta Jerina) collection for the Serbian issue of Elle magazine, 1969, Courtesy Museum of Applied Art, Belgrade

His most successful collection were three, presented between 1967 and 1969: Simonides, Stained Glass and Jerina. They were featured on many western fashion magazines, and marked a radical change of the concept of high fashion in socialist Yugoslavia.

Drawing for the Damned Jerina (Prokleta Jerina) collection, 1969, Courtesy Museum of Applied Art, Belgrade

Simonides was the first ‘haute couture’ collection of socialist Yugoslavia. It was presented to the Belgrade audience on 7 March 1967. The collection featured pearls, complicated embroidery and prints and simple, neat cuts, with more constructed ‘bell’ sleeves, inspired by medieval Byzantine clothing and serbian traditional attire. Stained glass and Landscape took inspiration from the coloured glass windows with Orthodox and Catholic monasteries. The collection was showcased at the luxurious fashion Feast of the Leningrad and the exhibition hall of the Belgrade Fair, and it was also screened in Zagreb and Ljubljana. Jerina, presented in 1969, included reference to the latest designs presented in paris by the Pierre Cardin, but was described as an ode to the legendary construction of the city of Smederevo, demonstrating how the designer was alienating aligning the meaning of his collections to the general promotion of the state put in action by the regime.