Archive for July, 2016

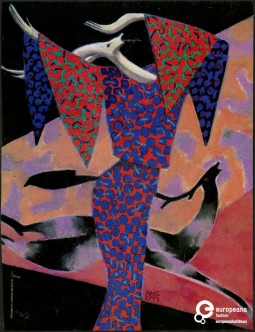

Lorenzo Mattotti

Illustrating fashion is a very peculiar act; while sketching is the earliest stage of the design process, when the idea gets the form of some lines on a sheet, fashion illustration calls for a completely different context and then, a different meaning. It is about retracing the idea behind a real dress, imagining a set and visually writing a story.

It is not necessary to come from inside the fashion world to be able to capture the intrinsic nature of fashion; Lorenzo Mattotti exemplifies the fact that what is needed is instead a good eye and an open mind. Mattotti started to illustrate fashion when the ‘Valvoline’ group, a collective of comics illustrators founded between 1982 and 1983 with, as members, Igor Tuveri (Igort), Giorgio Carpinteri, Marcello Jori, Jerry Kramsky, Daniele Brolli, Charles Burnes e Massimo Iosa Ghini, started participating to the pages of Vanity, the avant-garde illustrated fashion and style magazine founded by Anna Piaggi at the beginning of the 1980s.

Of the whole group, he is the one who has established the longest relationship with fashion; this, probably because it allowed him to explore some themes – above all the relationship between identity and performance – that are central for him as artist and for the mythologisation of fashion itself. He has recently declared, in an interview to the Newyorker: “Doing fashion illustrations is part of my work, but for me it’s all about women. When I look back at my work, I see images of women. It’s all about women—very pictorial women putting on dresses, putting on a show.”

Mattotti’s provenance from the world of comics shows in his approach to the actual clothes in the illustrations made for fashion. Clothes are, for him, a pretext to reflect on the formal composition of images, and on the possibility to build narratives around the encounter of a body, a personality and a dress. The worlds he portrays do not want to be true-to-life, nor his personnages are immediately recognisable as ‘humans’, as it is clear in the illustration made in 1985 for Vanity, featuring Missoni clothes.

His interest in the body and its materiality goes together with the necessity to portray the materiality of clothes and textiles. All his works show his great attention to prints, embroideries and textures, together with his will to place clothes in an imaginary setting, establishing interesting links between what is visible and what is imagined, between reality and utopia.

Lipperheide Costume Library

Both an international research library and the world’s largest museum collection of graphic works on the history of clothing and fashion, the Lipperheide Costume Library constitutes a milestone for fashion research.

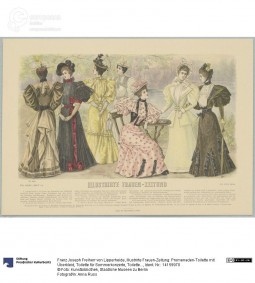

The Lipperheide Costume Library is part of the Kunstbibliothek, founded in Berlin in 1868. Its collection comprises now more than 40,000 books and magazines, from the sixteenth century to the present day, as well as paintings, manuscripts, over 100,000 drawings, prints and photographs. It encompasses literature on fashion from all over the world and of different eras, including magazines from the 18th century to today. In addition, the collection comprehends original prints and illustrations, as well as reproductions of artworks important to the study of costumes.

Plate from 'Illustrirte Frauenzeitung', 1894. Courtesy Anna Russ, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC-BY-NC-SA.

The Library was named Lipperheide Costume Library in 2006, after the Berlin publishers Franz and Frida Lipperheide, who donated their private collection to the Royal Museums in Berlin in 1899.

Franz founded his publishing house ‘Franz Lipperheide’ in 1865. A trained bookseller, he had previously worked for a fashion publisher that issued, among others, the magazine ‘Der Bazar’. His publishing house printed the magazine ‘Modenwelt’, focused on women’s fashion, which had great success and was eventually even distributed abroad. His wife Frida later undertook the direction of the magazine, which in 1974 included also news about entertainment, and was renamed ‘Illustrirte Frauenzeitung’.

'Les Coulisses de l'Opéra - Le Corps des Ingénus', coloured lithograph created by Joseph Bettanier, ca 1860. Courtesy Anna Russ, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC-BY-NC-SA.

To respect the wishes of its founders, the collection – originally established as an independent curatorial department within the Kunstbibliothek – has been preserved and made accessible to the public. It is possible to browse part of it on Europeana Fashion portal: this selection of 8000 objects includes photographs, drawings, illustrations and patterns from the 16th to the 20th century, in addition to the precious plates of the ‘Illustrirte Frauenzeitung’.

Visit the Europeana Fashion portal to find the beautiful pictures of the Lipperheide Costume Library and the Kunstbibliothek and discover this fantastic collection of paper fashion.

Femina

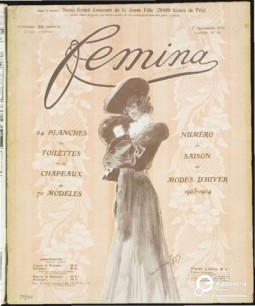

Subtitled ‘The perfect review for women and girls’, the illustrated magazine created on 1st February 1901 by Pierre Lafitte took its name from the Latin word femina, meaning ‘woman’.

Femina was the first French magazine targeting a female audience, consisting mainly of readers belonging to the middle class; central for the magazine was the support to Parisian fashion in the early twientieth century, which was advertised thorugh the pages as the most fashionable option for intelligent and refined women caring about their appearance.

The illustrations represented the main attraction of the magazine. On May 1st, 1903, Femina titled “Women Artists at the 1903 Salon” and dedicated three pages to the illustrations of Louise Abbéma, Louise Catherine Breslau, Camille Claudel, Maximilienne Guyon Louise Clément-Carpeaux, Laure Coutan-Montorgueil and Juana Romani. After a few years, the magazine cover, which had previously been mostly a reproduction of a photograph, started to be accompanied by a cartoon illustration in bi-chroma.

Anne R. Epstein, in her review of the book by Colette Cosnier, The Ladies of Femina, described a mystified feminism in the editorial direction of the magazine. Indeed, Femina was not born to be a feminist magazine but rather a woman’s magazine. The editorial strategy of Pierre Lafitte, the publishing director, was inspired by The Ladies’ Magazine, a successful English publication.

He envisioned a luxury magazine dealing with fashion trends, society and family. However, feminist topics of the time – including the claims of the suffragettes in England and the acquisition of voting right by the Danish women – were treated and discussed in the journal. Moreover, Lafitte used to give great prominence to leisure and sports in practiced by women and, from 1906, he launched The Femina Cup, a sporting competition.

In 1909, the French Academy raised the question of the election of female members: immediately Femina asked its readers to elect 40 writers, to fill an imaginary female academy and published on a double-page an illustration showing the 40 elected seats in the institution’s dome. After being suspended in 1917, Pierre Lafitte sold the journal to Hachette; the publishing house then merged Femina with another magazine called “The Happy Life”.

Visit Europeana Fashion portal to see more Femina’s images from our archive.

Europeana Fashion Focus: ‘Évêque’ ensemble, designed by Paul Poiret, 1907

The outfit is a summer ensemble composed by a dress and a bodice. The dress is made in linen and cretonne; it was designed in 1907 by french couturier Paul Poiret. The french word ‘évêque’ means ‘bishop’, recalling the proportions and overall look of the cassock used by members of the clergy.

The bodice is white, with small pleats on the front and flouncy sleeves that narrow from under the elbow to the wrist, and also presents some pleats. The skirt is composed by a belt, a first part with vertical stripes and a second with horizontal stripes, that hits the floor; the textile is printed with a particular technique, called planche de bois, which consists of a printing with a wooden board carved with the motif.

In 1907, Poiret launched the ‘colonne’ line, beginning his experimentations in alternatives to the current proposals for women clothing. The designs belonging to this line were characterised by a long and straight skirt, to which was attached a belt in gross grain; this belt was not only an aesthetic choice, but allowed to wear the dress without the need of a corset. In fact, in his autobiography En Habillant L’Epoque, the couturier declared to have ‘freed women from the tyranny of the corset’.

The object is part of Les Arts Decoratifs Archive. Take a closer look on the Europeana fashion portal.

Constance Wibaut

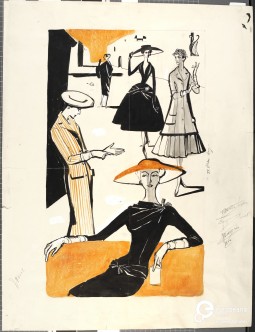

The Dutch fashion illustrator Constance Wibaut (1920 – 2014) once said that the hardest part in fashion drawing is ‘how to get chic on paper’.

In an interview filmed for the exhibition ‘Modepalezein in Amsterdam: 1880-1960’ held at Amsterdam Museum in 2007, she talked about her practice, explaining what she learned during her career (you can view the interview here). Constance Wibaut, who studied sculpture at the Nieuwe Kunstschool and at the Rijksacademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam, moved to New York with her husband just after the Second World War. There, In 1946, she found a job as fashion illustrator for the magazine Women’s Wear Daily.

Fashion illustration by Constance Wibaut, 1955. Courtesy Gemeentemuseum den Haag via Modemuze, all rights reserved.

At WWD she developed her signature style, drawing ready-to-wear clothes on a hanger for the magazine. The need to be precise and to include all the details, from the buttons to the stitchings – as they were important for sales – would have influenced her future illustrations, which were characterised by elegance and easy legibility.

Three evening ensembles by Dior in a fashion illustration by Constance Wibaut, 1956. Courtesy Gemeentemuseum den Haag via Modemuze, all rights reserved.

In 1953, Wibaut moved back to her native Amsterdam and started working as fashion illustrator for Elsevier Weekblad, later becoming fashion editor of the same publication. In Europe, Wibaut illustrated the creations of many of the greatest couturiers of the 1950s and 1960s, including Pierre Cardin, Cristobal Balenciaga and Christian Dior. Many of these drawings and illustrations, often sketched in the designers’ ateliers right after the shows, are now collected in the archive of Gemeente Museum den Haag and are part of Europeana Fashion collection.

Chanel, Dior, Jacques Fath and Madeleine de Rauch in a fashion illustration by Constance Wibaut, 1956-57. Courtesy Gemeentemuseum den Haag via Modemuze, all rights reserved.

In addition to her work as fashion illustrator, she designed costume designs for various plays and television shows and, from 1960 to 1967 she had been ‘Conseilliere de Mode’ for the Dutch Economic Association of Garment Manufacturers and delegate to the ‘Association Internationale des Industries du Vetement Feminin in Paris’. Since the 1950s, she taught fashion illustration in Universities and academies in the USA and the Netherlands and gave lectures on Costume History, Costume Drawing and Stage Design; she worked as lecturer until 1985, when she left fashion to focus on sculpture.

Browse the Europeana Fashion collection to find many of her illustrations depicting creations by Christian Dior, Cristobal Baleciaga, Nina Ricci and Pierre Cardin, to get a unique insight of a feminine point of view in the golden age of Couture.

Parades: Identity on display

Parades are celebrations filling the streets of a city with people marching together, for the most various reasons. They are highly designed events, in which costumes play a fundamental part in defining the tone and overall image of the celebration itself.

Parade with local costumes from Messologhi, Greece, 1936-1939. Courtesy Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation

Parades, above all official or military ones, represent the encounter with the necessity to give a ‘face’ to power and the interest in using the ‘spectacle’ to produce consent. For this reason, from the parades originated various ‘bidimensional’ materials that had the role of portraying an ephemeral performance, to record and remember it; these materials are what we use today to know more about these performances. In fact, the most direct and immediate source to get to know something about parades of the past are prints and, where possible, photographs; these materials, together with actual garments and props that survived in museum collections and archives, are for us documents of past practices and also fascinating postcards showing the different ways in which people used to colonise the streets of their city and shape their common national or group identity.

Tinted photo of men with costume from Pontus and a man with military uniform. Courtesy Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation

Even though it is excessive to say that parades can be read as quasi-fashion events, the similarities are hardly deniable. They are both highly controlled, from the timing and choreography to the dresses and walk, and serve to present something, be it a collection or a set of military values, and convey meaning. Fashion historian Caroline Evans has underlined the common features between the first fashion shows held at the beginning of twentieth century and military parades, highlighting the link between the two events, in which dress is central. The design of parade attires is very precise, and each detail has a role in producing the spectacularity of the march: the factors taken into account were multiple, from the sound of medals in movement, to the dimensions and look of accessories and insigna, to the effect of light on the different colours and textures.

Plates depicting uniforms and ‘parade attires’ are very important, not only to understand how the outfit were composed and what details differentiate roles and positions; they also give us information about the way each garment had to be styled and what kind of pose and ‘posture’ they requested, in order to perform in a successful way.

March to our collection and seek new stories about fashion and uniforms on the Europeana Fashion portal.

The Paper dolls of Anne Sanders Wilson

Paper dolls are two-dimensional figures representing a vast variety of subjects, as people, animals or objects. Printed or hand drawn, paper dolls were widely used throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as toys for children, or as a funny entertainment for wealthy adults.

In 1832, Anne Sanders Wilson used paper dolls to illustrate the tale of redemption of a ‘fashion-stricken’ young lady, Miss Wildfire. The paper dolls came each with a hat and eight different outfits, from a maid's dress in blue with a striped apron to a fancy dress in 'Vandyke' style, all in watercolour on card.

Paper doll's head, watercolour on card, made by Anne Sanders Wilson, London, 1832. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, CC-BY-SA.

These came alongside a manuscript called ‘The History of Miss Wildfire’, and were used to visualise the misadventures of the protagonist; she used to dress with fancy clothes, then she descended into poverty after the death of her father and was forced to earn her keep as a lace-maker. Eventually, she managed to ‘redeem’ herself with marriage and conversion to Quakerism.

Paper doll's costumes, watercolour on card, made by Anne Sanders Wilson, London, 1832. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, CC-BY-SA.

Anne Sanders Wilson’s paper dolls constitute a recollection of costumes from the second half of the 1820s to the early 1830s; they range from fancy, fashionable clothes to working class and occupational dresses. Despite their recreational purpose, these dolls, manufactured in London in the first decade of the nineteenth century, became a far-reaching mean to create fashion stories and contribute to the diffusion of styles.

Paper doll's costumes, watercolour on card, made by Anne Sanders Wilson, London, 1832. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, CC-BY-SA.

In fashion, in fact, paper dolls covered an important role in the diffusion of the latest trends. In this sense, paper dolls were used since the second half of the eighteenth century in fashion cities like Vienna, London or Paris. They were sometimes created by dressmakers to show current styles not only in clothes, but also in coiffures and accessories. For the speed with which printed fashion images could be distributed, paper dolls became a favourite medium to spread information about fashion, characterizing the period from circa 1825 to 1850.

Browse the Europeana Fashion portal to find other beautiful paper dolls by Ann Sanders Wilson or discover more examples of fashionable paper dolls!

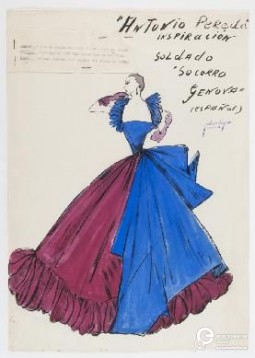

Pedro Rodriguez

Born in Valencia in 1895, Pedro Rodriguez became apprenticed to a tailor when he was just ten. While still a teenager, he was already designing on his own and, in 1919, he founded his fashion house, which was the first to be opened in Spain.

His work became very popular after a showing at the Barcelona Fair in 1929, making him especially known for his beaded evening gowns. With his elegant and classic style, Pedro Rodriguez seduced the high class of Barcelona and, during his career, he managed to gain international success, establishing himself as a reference in Europe’s Haute Couture.

Like his compatriot and friend Cristobal Balenciaga, Rodriguez moved to Paris at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. While Balenciaga remained in Paris after the end of the war in 1939, Rodriguez decided to go back to his native country and quickly started opening new boutiques, in San Sebastian and Madrid. In 1940 he also founded the Cooperative of Haute Couture, of which he remained president until his death; during his mandate, he worked hard for the promotion of Spanish fashion abroad. Unfortunately, the Spain that Rodriguez returned to was ruled by the authoritarian government of Francisco Franco, who caused a relative cultural and political isolation; this is probably the reason why Rodriguez’s reputation was largely confined to Spain.

However, a great commercial acceptance in the United States arrived when in 1952 an unnamed Spanish import/export house hosted a Spanish Festival of Fashion in Madrid to lure North American clothing buyers into Spain. The festival, which featured the work of Pedro Rodriguez and four other Spanish design houses, was the first attempt to market Spanish fashion to an international audience; Rodriguez was described as the preeminent Spanish designer working in Spain.

Discover more amazing images of Pedro Rodriguez on Europeana Fashion portal!

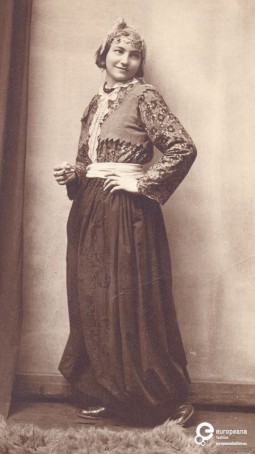

Strike a Pose. Fashion in portraits

‘Strike a pose’ is a very common expression in fashion, referring to the idea of ‘posing’ in front of the objective of a photographer. However, posing is not something we find just in fashion editorials; it is a sort of acting, performed by people in many portraits and photographs.

Group portrait of three girls in an outdoor environment in Lima, Dalarna, 1925-35, Courtesy Stiftelsen Nordiska Museet

These ‘representations’ are less directly linked to the fashion system; nevertheless, they have the capability to convey information about the complex and ever-changing relationship between people and their dress, identity and sartorial choices. Photographic portraits are fascinating as they are enigmatic. They are testimonies, incredibly valuable sources to study, understand and appreciate fashions and styles of the past, as they were interpreted and lived by people in their everyday.

Portrait of Mina Hadzi Paskovic dressed as a gipsy woman, 1931, Courtesy Museum of Applied Art, Belgrade

Looking at these materials, we can analyse customs and manners, even the personalities and attitudes of the people ‘captured’ in the shoots; why are they wearing those clothes? How did they pick them, and what do they mean for them? What do the clothes say about the time in which the photograph was taken, and about class, social status, history more generally? Every photograph tells a particular story, freezes a moment and allows us to actually see the way in which clothes were used and styled in real life: dresses and accessories are like props, and their very use, shown in the photos, becomes the material memory.

Portrait of a couple in the countryside of Lima, Dalarna, 1925-35, Courtesy Stiftelsen Nordiska Museet

Most of the times though, it is very difficult to be able to grasp the full story just by looking at a photograph. The relationship between a person and the clothes chosen for that photo is so intimate and linked to personal experiences, that it is hard to tell the real reason why that particular dress was selected to be immortalised in the photograph. Under this respect, the photograph in itself is a designed object, controlled in every part; it speaks about the character of the sitter, his or her way to be presented and to be remembered, and this is its most beguiling characteristic. Small details – the length of a skirt, the fit of a jacket or a dress, the expression of comfort or discomfort of the sitter, his or her position – are the hints to read between the lines and built a deeper and fascinating understanding of the story behind this alternative example of ‘paper fashion’.

The Europeana Fashion portal holds many of these precious objects: those presented alongside this article are but a few. Search our collection to find out more about these alternative ways of ‘seeing through clothes’.

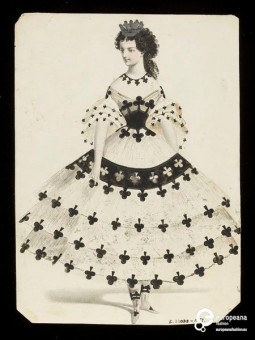

Dress to Disguise and Play: The Masquerade

The performative quality of clothes is so strong that it also create the space to become someone else, even just for a little while. Masquerades have been, for centuries, events designed especially to play this game, and costumes were its absolute protagonists.

'Queen of Clubs’, watercolour drawing by Jules Helleu of a masquerade ball dress, probably for Charles Frederick Worth. Paris, 1860s, Courtesy Victoria & Albert Museum, CC-BY-SA

The existence of masquerades – as designed social gatherings where the participants had to wear a costume – can be dated back to the 15th century; they started off as occasions organised in Europe to celebrate royal entries, marriages or dynastic events, then, from 16th century, they were popularised as public festivities. Far from being events reserved to the higher strata of society, these kind of festivals were to take place on the streets of the city and all the population could dress up, participate and perform a self other from their own.

For their allowed extravagance, masquerades were one of the favourite themes for plates and satirical prints, which usually took the fancy attires of the participants to the extremes, depicting grotesques scenes, funny accidents and nearly absurd misunderstandings happening during these times of joy and folly.

Philip Dawe, 'The Macaroni. A real Character at the Late Masquerade’, caricature, London, photo Dietmar Katz, Courtesy Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin CC-BY-NC-SA

Infact, women and mens used these occasions to put on the most marvellous and bizzarre ensembles, disguising their aspect as well as their identity – in some occasions, even crossdressing was tolerated. Playing with clothes functioned as a sort of social pleasure, allowing a degree of freedom that was unusual in society governed by wide differences between classes. Left aside for a day their ‘daily uniform’, everyone could disguise as someone else, helped by the possibility to accessorise the extravagant outfit with a mask, usually as elaborated as the dress itself.

The very nature of masquerades as more or less exclusive social events changed over time. With the birth of couture in the second half of 19th century, the name of some well-known designers became associated with some of the most exquisite example of dress chosen by society ladies to take part in these events and ‘steal the scene’. The images illustrating this article show some designs by Charles Frederick Worth, who collaborated with famous desinnateurs to produce these drawings; these sketches had to be incredibly detailed and well-done, to tackle the curiosity of his demanding clients.

'Eve and the Serpent’, watercolour drawing, by Leon Sault of a masquerade ball dress, probably for Charles Frederick Worth. Paris, 1860s, Courtesy Victoria & Albert Museum, CC-BY-SA

Worth’s designs for masquerade were especially appreciated by Empress Eugenie, who used to commission her ‘fancy’ outfits to the couturier – usually with very short notice and great expectations. Empress Eugenie held numerous masquerades during the 1860s, and all the society ladies of Paris followed her ‘fashion leadership’, also turning to Worth for their own attires.

We can live the memory of these marvellous events through the drawings of these dreamy dresses: discover some of these designs on the Europeana Fashion portal.